In Conversation

By Ōtepoti He Puna Auaha | Dunedin UNESCO City Of Literature | Posted: Monday Oct 06, 2025

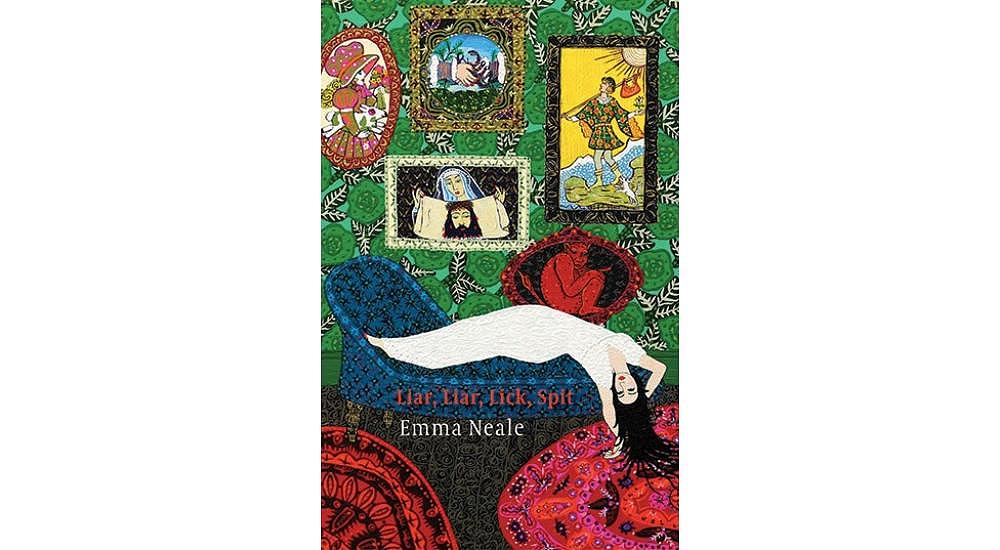

Grace Yee & Solli Raphael on Emma Neale’s Liar, Liar, Lick, Spit (Otago University Press)

Grace Yee: I want to begin by thanking Melbourne City of Literature and Dunedin City of Literature for continuing to support this conversation – particularly after our withdrawal from the Bendigo Writers Festival following the Code of Conduct censorship debacle. I also wish to acknowledge Jacinta Le Plastrier’s contribution and generosity, and the fruitful discussion the three of us had about Liar, Liar, Lick, Spit two days before the festival. It is unfortunate that Jacinta is now unable to join us in this conversation.

Usually, I prefer to jump into a book unencumbered by preconceptions and other people’s opinions. However, because Liar, Liar was all over the news earlier in the year after it won the Mary & Peter Biggs Award at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, I had already read some reviews, and these informed my expectations. The reviews I read describe the book’s reach in terms of ‘untruths’, ‘delusions’, ‘mis-rememberings’, etc, and one reviewer refers to the collection as ‘a book of lies’. According to the blurb, Liar, Liar combines ‘a personal memoir of childhood lies with an exploration of wider social deceptions’. While there are indeed poems that take lies explicitly as their subject matter – and these range from childhood porkies to relationship infidelities to family skeletons to lies under torture – the collection is more broadly and complexly, about how people show up or perform in the world, perceptions of other people, and the elusiveness of truth, among other concerns; and notably, there are several poignant poems about loss. In my view, Liar, Liar is so much more than ‘a book of lies’: in light of this, its packaging could itself be seen as misleading, a deception of sorts, though it’s not clear if this is intentional.

What were your first impressions of the book, and how did they evolve as you read?

Solli Raphael: What strikes me the most through our conversations is how contrasting our approaches were going into Liar, Liar, Lick, Spit, and how that shaped our musings and the light in which we viewed each piece.

I decided to go into Liar, Liar about as blindly as one can; without even peeking around at the blurb. Sitting on my desk for a few weeks before being read, the title rolled around on my tongue, and I pondered: Who is the liar? What is the lie? In that sense, my only preconceptions centred around just how closely the title might be related to the work.

I agree, Liar, Liar extends well beyond lies, but its breadth was neither clear nor coherent in narration early on. The blurred and, at times, wavering space between reminiscences and observations morphed and evolved into an understanding that the subject matter of ‘lies’ is both present and partial. My first impression of Liar, Liar was that the title was indeed closely related to the collection. The opening piece, ‘False Confession’, paints a picture with intensity. However, the following pages shift the tone and unravel memoir-like tales of lies told and witnessed by the subject. Perhaps the pivotal piece for me was ‘Split Decision’, when my understanding at that point was flipped on its head, with the piece conveying a ‘what could have been’ message had a lie been told. From there, the memoir theme continues but slowly splinters off into an array of directions from the subtle to the sinister, referencing, as you mentioned, perceptions of others and also loss.

Was there a poem or point that stood out from your reading of the book when the contents challenged your preconceptions?

GY: My preconceptions of the book were continually challenged reading the collection. I found that I was subconsciously trying to ‘fit’ all of the poems into the ‘book of lies’ frame that I had consumed from the reviews. In my reading, many of the poems did expand to accommodate. The concept of ‘untruths’ is, after all, monstrous and knotty, and lies and deceptions rest on the slipperiness of language - where better than poetry to explore? The poems in Liar, Liar inhabit a vast spectrum of human duplicity and associated implications and moral conundrums: scepticism, mistrust, abuses of power, powerlessness, disillusionment, secrets, self-deceptions… I see it as a collection about how truths may be dissembled, concocted, ineffable, remote. What pervades the collection most conspicuously, in my view, is an aching sense of what’s missing and unpinnable, of loss.

Such elusiveness is compellingly evoked in the opening poem, ‘False Confession’, inspired by the Kurdish poet and journalist Ilhan Sami Comak. This poem characterises truth as the poet’s ‘convictions’, ‘broadcast’ ‘across the oceans, the continents / and the forests, bristling green’... ‘as solid as eyewitnesses’. Truth is portrayed as pervasive, ‘like a mist of pollen’, but like this mist, does not have sufficient weight to prevail or anchor.

‘False Confession’ is followed by ‘Porky’, a confessional narrative (which I understand by the blurb to be one of the author’s memoir poems) about a child who tells fibs about fish and chips and hitting her baby sister, who when discovered, feels her own ‘presence thin and thin’. ‘Porky’ begins with an epigram by poet Joseph Brodsky: ‘The real history of consciousness starts with one’s first lie’. On my second reading of Liar, Liar I read the book in sequence, and was struck by the juxtaposition of ‘Porky’ and ‘False Confession’: a poem about childhood fibs immediately after a poem about a man tortured to make false confessions and imprisoned for thirty years. I found this a bit jarring initially, but have come to the conclusion that their placement is meant to indicate the considerable breadth of the collection.

How did you feel about the positioning of these first two poems? Were there other pairings or sequences that gave you pause?

SR: Diving straight into ‘Porky’ after ‘False Confession’, I found myself circling back to the lines of the first and deciding to digest before continuing. Regarding pause, two other poems come to mind: ‘Tyranny’ and ‘Split Decision’. Tracking the trajectory of name-calling and the perspective of childhood untruths, ‘Tyranny’ takes a turn and grasps a more complex meaning by seeking to understand why such untruths are said. A message supported by a repeated use of the statement: ‘do unto others, as you would have them do unto you.’ That was perhaps the first page on which I consciously noted the shift beyond fibs and false confessions. ‘Split Decision’ on the following page left me a little perplexed, suggesting that a lie should have been told, with the final statement, ‘where perhaps he might have saved their marriage / with a loving / bridal white lie.’ For me, ‘Tyranny’ and ‘Split Decision’ gave pause not as a jarring sequence but with the further consideration they offered.

Several consecutive poems that stood out to me were ‘Pandora First Gets Feminism, Age Ten’, ‘Pre-teen’ and ‘&’. The first of the three observes Pandora home alone for the first time, searching the house and finding erotic, female-centred magazines. When confronting her father, he responds that his friends made him take them, a statement that it appears she doesn’t believe. Ending with the line, ‘learning her father was never really a god’, it wasn’t clear to me if this poem is mythology-inspired or a figurative depiction of Neale’s recollections … perhaps a composition of both. On the other hand, this poem follows 'Tyranny' in exploring the reasoning behind lies and the powerful messages we can take away from those discussions.

Although I had an understanding of the collection’s breadth by this stage, ‘Pre-teen’ didn’t appear to fit into the ‘book of lies’ frame that I, too, had adopted. I initially found its connection to the book’s theme hanging by the opening Goan proverb: ‘Truth is twelve years old’. With consideration, the pre-teen style and confidence expressed in the piece could reflect the subject’s true self, a space clear from lies and deception. However, its position after ‘Pandora’ and followed by ‘&’, which I first read to have a less apparent relation to truth or lies, was rattling. I would say that the pause resulted from both the positioning of these poems and my own positioning and frame of mind.

Which poems stood out to you? Were there any particular pieces you revisited?

GY: If we consider the ‘personal memoir’ approach, and the semantics of ‘truth’ and ‘lies’ more broadly in Liar, Liar, poems like ‘&’ and ‘The Piano Tuner’ – both of which suggest performance or by association, modes of concealing truth – can be accommodated.

There were several poems that I revisited; my favourites were towards the end of the book.

‘Wishing he’d declined cocktails, stayed at home to read Janet Frame’ spoke to my introvert self. At the party, his attendance a self-betrayal, ‘His head hums like static on a screen’. I could totally relate to the relief of escape, too: ‘he slips free into skinny streets, / the trees like cut-outs / stapled to the dark’, and of returning home ‘to where a silence hangs / plump, wine-heady, sweet’, to the blissful luminous sanctuary of oneself: ‘and soon a cube of light hovers / a mandala between his eyes / with the after-brilliance // from a turned end-page.’

‘Sempre marcatissimo’ and ‘Dreams are the dark glasses and heatproof shell the mind wears when the truth is a hot, burning ball of plasma and at least sixty-seven known elements’ are standouts for me. I read ‘Dreams are the dark glasses…’ as a conversation between lovers that portrays the slipperiness of communication even – or perhaps, especially? – with those we are closest to: ‘At first, she could have cried, for how entirely / this seemed to miss the point – but you know, / love is its own strangely layered card game’; ‘All the grief was there - / but as beetles, burrowing.’’ In my view, ‘Sempre marcatissimo’ is the strongest poem in the collection. Its pace, as the title suggests, is strong and accented all the way through, and the rhythm and tension compelling. I held my breath from the opening strings to the heart-rending closing scene where the child, instinctively aware that her father is waning, succumbing to long-held grief – ‘his presence is already diminished’ – attempts to hold him in the present moment by ‘play[ing] and replay[ing] the opening bars’ ‘as hypnotised as a child / with a banded sphinx moth in a lidded jar: / transfixed by its ardent battering.’ How many of us as children wielded distraction tactics not unlike this when we sensed our parents’ burgeoning griefs and tensions? In many ways, the final stanza in ‘Sempre marcatissimo’ epitomises the themes of loss, not-knowing, and the elusiveness of truth (including other people’s truths), that pervade the collection.

What were your highlights?

SR: In returning to the ‘jarring sequence’ discussion, I found a greater understanding of each piece when revisiting one at a time. Perhaps the benefits of rereading the collection were emphasised by my initial diving into the book without a prior understanding of its themes. I might also add that upon reflection, I had searched for the deceptive context and fabrication of each piece as I made my way through the collection. Once I put this ‘search’ aside, ‘&’ spoke to the performer in me; the opportunity performance offers to explore truths in the performer’s identity and the genuineness in stories. Performance is also a chance to lie, to be someone else and embellish. I was enthused by the visual and figurative representation portrayed, ‘yet when I see / its curled strand / I remember cellos, / a cellist & the small / upflick flourish / of a finale bow stroke,’. I love the intertwining of the imagery and the way these perspectives foster the narrative of the poem – ‘when a young / cellist’s mother / bends above / a borrowed pair / of shiny, lace-up / recital shoes / while she hums / first we do / this loop / & / then we do / this one too’. The richness in meaning and its deepening at the end left me with an understanding of how this poem adds to my perspective of the collection.

Another highlight of mine was ‘Mask’. Beginning with opening lines that I quite enjoyed – ‘If every fiction tells a secret / without revealing it,’ – in my view, this poem is a statement piece that doesn’t shy away from delivering a bold expression of the collection’s themes. I read ‘Mask’ as a blend of memoir, with the lines ‘through white wax paper / that conceals an aniseed sweet,’ and ‘from the moment / an infant first discovers / the power in a mock cry, / it is given / a false identity’ – yet it also swirls around the motifs of performance, deception and loss.

My highlights extend beyond these, including ‘Sempre marcatissimo’, which was also a standout for me as one of the strongest poems in the collection. It doesn’t just reference Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings; it conveys a similar emotional intensity.

From my perspective, there isn’t one way to approach Liar, Liar, though its potency increases with each revisit, so additional read-throughs are a must. Perhaps part of its merit lies within the breadth of perspectives and the number of times they left me provoked and pondering.

Grace Yee is a poet, writer and researcher. She was born in British Hong Kong, grew up in Aotearoa New Zealand, and now lives in Melbourne, Australia, on Wurundjeri land. She is the author of Chinese Fish, which won the Victorian Prize for Literature and the Victorian Premier's Award for Poetry in Australia, and the Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. Chinese Fish is published by Giramondo in Australia, and is slated for publication with Akoya in the UK in 2026. Her second book, Joss: A History (also Giramondo), was released in June 2025.

Solli Raphael is an award-winning author and poet, advocate and acclaimed keynote speaker. A former ambassador to many charities and non-profits, Solli runs Earth Enablers, an environmental conservation organization, World Of Poetry, a collective designed to amplify poets’ voices, and The Best Part, a social movement utilizing the power of words to spread positivity. Despite being 20, Solli has spent almost a decade pursuing his passion for starting thought provoking conversations and instigating change in the areas he feels are critical for attention and action. Solli has authored four books, which have received accolades for their capacity to engage children and teenagers educationally. His newest book, Starlight, aims to guide self-discovery and self-expression in children and teenagers.

Solli spends most of his time on the road, speaking at schools, universities, events and businesses, as well as being regularly featured on radio and TV shows, in printed media and books. His work has reached a global audience of two billion people.