Vaughan Rapatahana reviews Funkhaus by Hinemoana Baker; Upturned by Kay McKenzie Cooke; AUP New Poets 6 (Ben Kemp, Vanessa Crofskey and Chris Stewart)

By Vaughan Rapatahana | Posted: Monday Oct 05, 2020

Funkhaus by Hinemoana Baker (Victoria University Press, 2020), 79pp., $25; Upturned by Kay McKenzie Cooke (The Cuba Press, 2020), 98pp., $25; AUP New Poets 6 (Ben Kemp, Vanessa Crofskey and Chris Stewart) (Auckland University Press, 2020), 114pp., $29.99

These are three new collections of poetry, all from 2020: five poets, three of whom are categorised as ‘new’ or early in their careers as poets.

Across these three volumes, and even within the Auckland University Press collection, there is tremendous variety with little in common overall. Except that they are written largely in te reo Ingarihi, with the exception of some snippets of te reo Māori.

The poetry, tetoikupu, of Hinemoana Baker is somewhat abstruse, almost as if written in their own secret code. It is difficult to get a grip on some pieces after only one reading. Take, for example:

I’m gonna heist my hands up

Grandstand and handstand

Heels bruise your spruced walls

Bark at your dogs, farm you out

My op-eds inject you

My stop signs forget you

My wood in your box

My grandfather clock

(from ‘Narcissist dips a finger’, p. 33)

Nevertheless, I found that the more times I read a poem, the more it gave back to me. More, the Notes give some context, as in the tribute poem ‘Mother’, which we learn was written in response to the conflagration at Tapu Te Ranga marae in 2019.

And if we look more closely, we see that Baker does offer us a clue to this cryptography. The initial pages of the book quote from Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry: ‘… nostalgists hate poems for failing to do what they wrongly claim poetry once did’. Which is, I guess, to be linguistically accessible.

Yet if we fine-tune through the initially perceived static on the pages, we are rewarded with full-on talkback, as in:

Oh Language you soccer fan I still long for you

even after everything we’ve been through.

(from ‘Waitangi Day’, p. 44)

Baker is currently stationed in Berlin and the German ambience comes through in several poems, both manifestly and latently. I am sometimes reminded of passages from fellow German language writers Franz Kafka and Robert Walser, where aspects of paranoia and the bizarre produce a distinctly odd patina. For Baker, too, language is always something that keeps us guessing:

Language is a flute, a lily,

a chair overbalancing,

a church we teeter

on the threshold of.

(from ‘If I had to sing’, p. 15)

Baker plays around also with alliteration, internal rhyme and even stream of consciousness, as in the excellent prose poetry of ‘Aunties’. Effective imagery conjures up feelings of yearning:

Yes even my fingerprints

Want my autograph

(from ‘Narcissist at lunch’, p. 34)

and

Behind us a door aches shut.

(from ‘He kanohi kitea’, p. 56)

There are surprising turns too:

The floor is so cold it could be old cocoa.

(from ‘Filling in the grave’, p. 55)

and:

Dog tongue

a hot fish I catch

between fingers.

(from ‘Tongue’, p. 66)

In these poems we have the work of an intelligent, enquiring, sometimes angry, on-the-edge poet. In her mihi, Baker references ‘the last hard five years’: there are issues with itinerance, illness and identity infiltrating much of the work. But the poet can also access the humorous and the loving, as combined so well in the canine tribute ‘Tongue’.

These poems have been described as ‘unsettling’ with reference to the wide-ranging topoi the reader encounters here. But I wonder, as I continue to reflect on this new collection, if ‘unsettled’ is a more appropriate term.

Kay McKenzie Cooke also writes poetry stemming from a deeply personal place and indeed, some of her inspiration stems from her time in Berlin—though that is where her poems’ similarity to Baker’s work ends. Cooke’s lyrical poetry is always easy to read and understand, quite the antithesis of the other part of Ben Lerner’s quotation: ‘avant-garde poets hate poems for remaining poems instead of becoming bombs’. Cooke’s verse is not incendiary, but it is by no means placid and flaccid either. In self-referencing poems such as ‘Many moons ago, Maurice,’ ‘Being there’ and ‘Too far’, there are plenty of vigorous barbs. Here for example:

I decide I need to channel my inner diva:

bitch, to be unafraid

to say fuck you …

(from ‘Too far’, p. 57)

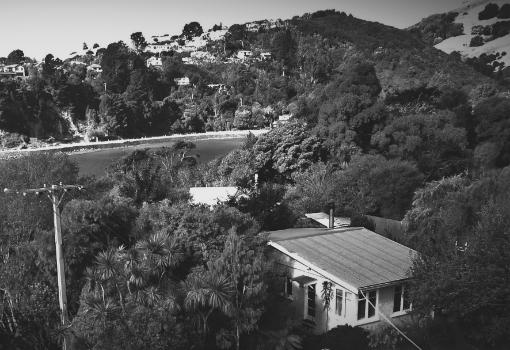

Cooke writes especially well when it comes to nature and her local Te Waipounamu surroundings, with one section, in which the setting changes rather abruptly, revolving around her visits to Berlin to see her son. Her poems are uniformly short and precise. There is a sentimentality through much of her oeuvre, while some of her poems are also rather moving, as in the reflectively sad memory of her mum, ‘All her calendars still said April’. Cooke saturates her verse with memories of her upbringing, of her whānau, of past visitors and vistas.

Cooke employs some awesome imagery and is ever ready to employ the tripartite force of metaphor, simile and alliteration, as for example in the poem ‘Turn of events’:

as perfect as a prancing pony.

(p. 55)

and these lines from ‘Foxes or squirrels’:

I am eating the language of the ocean …

eating the language

my granddaughter speaks.

(p. 60)

However, her lines are not always warm and inviting. In ‘Death rattle’, stars are:

as rudderless

as space junk

veering deeper

into a universe without mirth.

(p. 77)

In the accompanying The Cuba Press flier, Vincent O’Sullivan notes that Cooke brings ‘such shine to the ordinary’. Here is an entire poem that encapsulates her considerable craft:

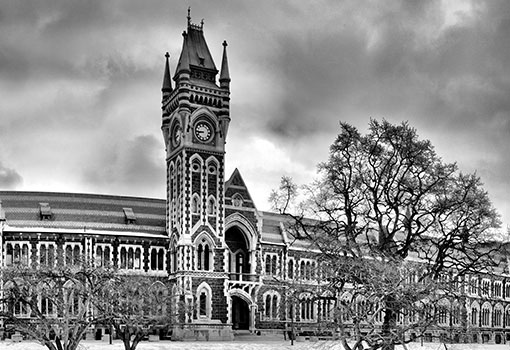

Nor’easterly

For days now

the unpegged washing of snow

has lain in the mud of Dunedin’s hills.

where a giant hawk of cloud

lifts off, in its talons

Mount Cargill, a sag of grey.

If I could I’d breathalyse this nor’easterly

to prove how full it is,

of Antarctic ire, how merciless

its gathering raid and quest,

to assassinate,

its intention to behead

every flower in its track,

to shatter

the frozen bones of birds.

(p. 18)

I would like to think Hinemoana Baker and Kay McKenzie Cooke sometimes might meet up in Berlin to have a kōrero, eh. Ko rua ngā kaitito Māori rawe tūroa. (Two fine, established Māori poets.)

Vanessa Crofskey is the clever centrepiece of the AUP New Poets 6 collection. Ben Kemp and Chris Stewart act staunchly as sentries in this compilation, much less as distinctive. Crofskey never hesitates to be direct, while her willingness to experiment with formats as varied as black-out poems, fold outs, Post-it Notes, recipes, splayed words that inhabit Excel charts and ledgers, as well as more ‘traditional’ lines on the page arranged in something like stanzas, create her singular set of pieces. Like Baker (who is an accomplished musician), Crofskey also travels well beyond the printed page: she is a spoken-word performer, a sculptor who assembles poetry upwards and outwards into three-dimensional strata.

More, Crofskey paints plangent multicultural portraits, most especially regarding her own sense of identity dislocation. The excellent ‘The capital of my mother’, for example, consistently depicts this haze:

I cannot find home except the sense

of somewhere I can’t reach

(p. 61)

And as with many, if not most multi-ethnic individuals, she encounters and exposes the discrimination still involved and unresolved in this country. It is a shame that her entire tour-de-force black and white assembly of New Zealand arrival and departure cards is not available for inspection—rather than the one-page sample here. The complete poem reveals the small-minded prejudices of members from the dominant culture when they attempt to categorise and, in so doing, derogate Asian New Zealanders.

Even more alarming are the banal sexual stereotypes lusted after by many of the males the poet has encountered, as in ‘To all the boys I’ve loved before’. And sample this candid comment from the frank ipseity-searching ‘Dumplings are fake’:

my best representation is in a section of pornhub

where all the skinny asian girls and the mixed chicks don’t speak

have big tits, and white men cum all over their faces.

(p. 33)

Vanessa Crofskey is a major talent, and her first solo poetic edifice cannot be far away from completion.

Ben Kemp—who is also an adept musician—harmonises distinctive and delicate Māori–Japanese riffs: he sees several parallels between traditional indigenous cultures, as in poems ‘Food to song,’ The Japanese moko’ and ‘Two vignettes of a warrior’, where he juxtaposes both. Indeed, the very first line in the first poem of this book is:

Japan is delicate,

(from ‘Juni-Gatsu’, p. 3)

Kemp’s pieces are carefully wrought and thought out. Places and personalities are described in considerable detail. I wager that Kemp puts a good deal of time into crafting his mahi. It is also good to see Kemp’s acknowledgement of the influence of Rore Hapipi (Rowley Habib) on his corpus. Hapipi too was a deep-thinking artist.

Kemp’s entire set of nuanced poems reveal themselves as koan-like throughout. In places he is an aspiring mystic, most especially in the longer piece ‘The essence of I (Ode to Walt Whitman)’ where he patiently points out:

I am waiting to be a river …

One day I will journey to the sea,

become that river and dissolve into the essence of it.

(pp. 23, 25)

Kemp gently brushes Ukiyo-e stokes of imagery throughout his display, in the lines:

& over the bridge with wide hips & feet resting in a puddle …

(from ‘Juni-Gatsu’, p. 4)

and

the mud giggling though my toes.

(from ‘The essence of I’, p. 22)

Here we see his dexterity across the page, noting how the white spaces are as important as the deliberate text placement:

Oto

(Sound)

As the cherry blossom falls in acid rain

my eye bursts into sketches of

red ink and

bamboo

and Meiji Jingū,

with white-washed pages and a delicate spine,

like a leaf in one’s fingertips under a sun

Our knuckles were white in 1945

flipping glances,

and leaving behind a whole generation

of stark, wrinkled branches

and solace …my love …

For only after 8am and before 3pm, will I pray

like buckled bridges

and twisted metal …

silent for now but still breathing

feathers tickling their swirling lips,

with a twist of sea eggs.

(p. 11)

I now look forward to his Papua New Guinea-influenced set of poems. Tēnā koe, Ben.

Whereas Vanessa Crofskey stretches the boundaries as to what a poem is ‘supposed to be’ and Ben Kemp transports the reader as he succinctly melds locales, Chris Stewart is focused on domesticity (he was a house-husband for some time.) Stewart writes finely crafted paeans to his young children and poems about the concomitant nurturing issues, from the chronic lack of sleep to teething problems and hospital visits with a sick child. Whānau and whanaunga is this poet’s sometimes austere cynosure: his is a loving paternal and filial role funnelled into his poetic craft.

The accent on sleep deprivation leads to hypnagogic poetry at times. In the poems ‘Like stone flowers a dead man’ and ‘My father the elephant’, slightly surreal images cascade throughout the pages. Indeed, his poem ‘You have too many dreams to be asleep’ gifts us the following lines:

after you wake three times

three hundred and sixty-five times

you cannot close

your eyes at home …

in a year of sleep you never complete

a dream

(p. 75)

Stewart, like Cooke, has metaphorical mastery and simile savvy. In ‘A tooth emerges’ he writes:

now I am a sore tooth pulled

from a soft bed

(p. 76)

and, in ‘Inflammation’:

nurses buzz off without saying

how long they leave us

down corridors skinny as

your trachea becomes

(p. 85)

And here, in a rather sweet and sour note:

a baby waking at night is

a lick of lemon

(from ‘I have no juice for you to suck’, p. 79)

Stewart’s past continually informs his present: reminiscences pertaining to his parents—and there are several here—become reflections on his role as father and husband. A poem like ‘The history of his bridge’ effectively translates this time travel:

We remember the flood. He shadowed us

rain-soaked children in the doorway …

Years later, torrents dam into soft rivers …

In the rain. His footmarks

gather no water.

(p. 90)

Finally, Stewart’s intense verse completely belies what he writes in ‘Male seahorses bear the young’:

Bigger fish told me when you have children

your life is over

(p. 82)

Far from it! Stewart, like his fellow poets in the AUP collection, are at the beginning of their poetic journey. I am most interested in reading his next family-focused selection as his children grow and as he manages to recapture some sleep.

There we have it. Five fine poets and three fine publishing houses. A diverse range of experiences—many international. A variety of approaches to composing a poem and indeed to defining what a poem ‘is’. A selection of poets extending from those who have published several collections to those who certainly will. This country is a veritable fount of dynamic literary prowess.

https://landfallreview.com/he-whenua-waimarie-a-lucky-country/