Listen, Memory

By David Howard | Posted: Monday Mar 02, 2020

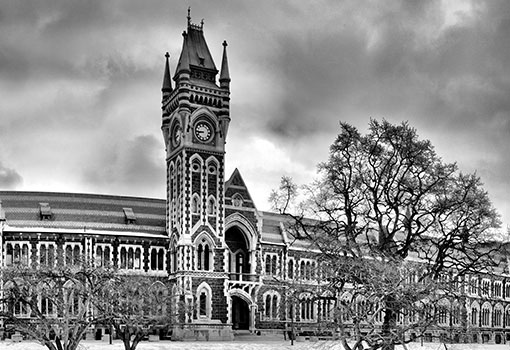

In September 2019 David Howard, representing Dunedin, took up a UNESCO City of Literature Residency in Ulyanovsk, Russia. His project, the church that is not there, organically divided into a triptych. In the left ‘panel’, resurgent trees, lyric fragments were inspired by the 1905 and 1947 clockwork figurines made by the Morozovs and now displayed at the Ulyanovsk Regional Puppet Theatre. The central ‘panel’, roll of honour, references Russian poets. The right ‘panel’, Sakharov meets Oblomov (1943), imagines that the (future) creator of the bomb visits Oblomov in the house of the author Ivan Goncharov.

To arrive is to arrive at a departure, ta-daaaa! The coordinator of Ulyanovsk City of Literature, Gala Uzryutova, walks me to a park opposite the old house of novelist Ivan Goncharov, the author of Oblomov, a novel that will loom large in my project. But I don’t know that yet, nor do I understand how being here will reconfigure the co-ordinates of my self. I do not fill Goncharov’s shoes, but I do try on Oblomov’s slippers: they are made of bronze. There is a yellow lime-tree leaf over the left one. How did it get so late so early? I walk back to my hotel, slip-sliding away from one past into another. So this is what bronze feels and sounds like, I think, taking another step.

The next day I visit the Regional Puppet Theatre to engage with wooden clockwork figurines made in 1905 and 1947 by the Morozov family. The two dioramas show different universes: one pre-revolutionary, one post-war Soviet. Here is a task for language, to measure the distance between them and to make that space oscillate. I begin to speak Russian with a New Zealand accent.

But I am not at the bottom of the world, squatting in the margin of the universe. No, I am ‘all over the place’. And I inhabit multiple time zones simultaneously. My first weekend here is marked by a reading, near a statue of Clio, in Karaminsky Park as part of Municipal Library event. While the Muse of History watches over us like a suspicious grandparent Sergei Gogin translates my words: they go out over the locals who nod, applaud, wait for either more or a merciful end, I’m not sure. But the response that stays with me comes when a sparrow that could be from New Zealand hops towards me. Yes, in Lenin’s birthplace!

Continuing to research, I visit the museum of the cartridge factory where Andrei Sakharov worked for the Great Patriotic War effort in the early 1940s. I see how to draft a dialogue between the father of the bomb and that superfluous man the fictional Oblomov was. Afterwards, no boatman, I follow the Volga River’s current from a stony bank. When I was a child my father taught me how to skip stones over the rivers of Canterbury. Fifty years and nearly 16,000 kilometres later one of those stones has dropped into the Volga alongside Ulyanovsk. I bend, as if in prayer, to recover that stone from the shallows. My guide Gala, the translator Olga Turina, and the sculptor Dmitry Potapov look on. What in God’s name is he doing? It used to be Lenin’s name that was ‘taken in vain’.

How to move on without staring over my shoulder, feeling my shirt collar stiffen with the formal starch of the past? Perspective modifies who you are when both the historical and the geographical scale is so great. We are walking a stretch of water 40km wide that is straddled by the second longest road bridge on the European continent. That’s one challenge, what has brought me here is another: how to spin language in a poem so that it lifts off paper like a skipping stone over water?

How to lift off? I hazard a guess when I deliver a keynote at the opening of the “Lipki” International Forum of Young Writers, addressing over 150 young writers, I speculate that a writer has to move from invisibility to visibility and back again. I maintain there are also inner and outer aspects of invisibility: how not to be seen in the work and how not to be seen in the world. Ego-driven ambition is essential to public success, yet it must be overcome while making the work because it obstructs perception, and a compelling work leaps from perception to perception – that is why and how it appears new. While it sounds (and often feels) tenuous, a writer needs to attend to the work before it is made, by listening to silence, summoning the work into being. Inspiration is the name for a privileged kind of listening.

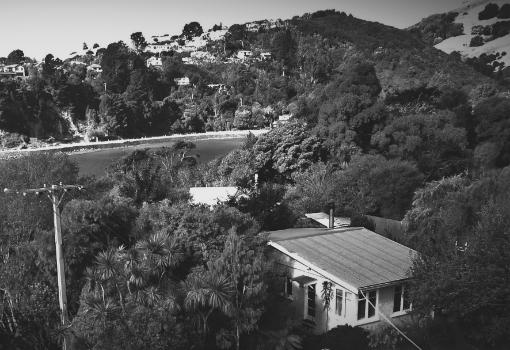

I say that we should consider the value, while gathering material, of not being seen by others. Yes, I nod, I learnt this early; when I was eleven I took up a paper run. I would cycle around the eastern suburbs of Christchurch – already one of the poorest areas in New Zealand – and found I was invisible. People carried on conversations with me in ear-shot; they’d be in the garden arguing while I paused at the mailbox. I got to hear a lot of home truths.

But once the work is made the writer has to be seen and heard so (in turn) the work can be. A few of the audience nod – finally, he’ll say something useful – then they shake their heads in dismay when I say that I chose not to do this for nearly thirty years, becoming known as ‘fiercely independent’. God, what is he on about? Well, my prolonged invisibility let me shape a distinctive body of work without external pressure. Yet I lost a lot of opportunities because of it. For most young writers (they stir in their seats) it is better to set off on that long walk through the minefield of networking, during which many false steps threaten.

I close with a few cautionary words: the most prominent author is also the most dangerous for a young writer. They may praise your work but they will never let you threaten their supremacy; they rarely acknowledge (living) equals only followers, so you will be expected to act as a cheerleader rather than as an independent thinker. It’s better to move with and towards those you respect regardless of their (lack of) status. Trust is the most wonderful catalyst for growth. If you do this you will never act in bad faith. There is staccato clapping, then it is continuous if brief – like all attention.

But it’s a new day. The tireless Sergei Gogin is chairing the Ulyanovsk English Club. Who, from New Zealand, should we read? I shiver. I am fifteen again, reading Owls Do Cry in a tiny bedroom of one of the poorest suburbs of New Zealand, yet the walls fall away and the threadbare sheen of my street disappears as I turn each page: Read Janet Frame, I say, and younger Dunedin authors like Lynley Edmeades, Emer Lyons, Emma Neale, Robyn Maree Pickens, and Sue Wootton. The notebooks are opened. Afterwards Sergei takes me to see a play from the company ‘Enfant-terrible’. It is an allegory about exploitation and consumption. I can almost hear the words ‘Lenin’ and ‘God’. But I taste vodka because this drama has the astringency of strong spirit.

Time may be an illusion but, if so, the illusion is over. Forty eight hours before I am supposed to fly out of Ulyanovsk, the UNESCO Creative Cities Space is opened with a performance of Sofia Filyanina’s suite roll of honour: a setting of eleven fleeting lyrics by me, each section references a Russian classic. As Sofia conducts I feel myself beginning to levitate like an anonymous figure in a Chagall painting. Soon enough I am over Moscow, heading for London. From a long way off I hear applause. Thank you, I sigh, thank you.

https://www.anzliterature.com/feature/listen-memory/