Much-loved bard travelled a hard road

By ODT | Posted: Thursday Nov 23, 2023

Otago’s own Gaelic bard, Angus Robertson, has been rescued from obscurity and his literary achievements are about to be recognised, Alison Thornton writes.

Much-loved bard travelled a hard road | Otago Daily Times Online News (odt.co.nz)

When Angus Cameron Robertson (Aonghas Camsron Macdhunnchaidh) travelled up Otago Harbour in a sailing ship in July 1899, he was chief officer under Captain Allan.

They had agreed that he was ending 20 years on the seas in order to "better himself" and settle in Dunedin. This was to be his new homeland. He was in his 32nd year.

Robertson had left home at 8 going on 9 years old, after his father had beaten him so severely for coming home late that for the young Angus there was no going back.

Broadford on the east coast of the Isle of Skye, Scotland, had been his home. His father’s lineage as a bard went back a thousand years. His mother was likewise a bard and a sweet singer.

Angus had grown up totally in the Gaelic-speaking world of Skye, and then on the Isle of Lewis across the Minch in the Outer Hebrides, which he had reached as a stowaway.

Three years on the herring fishing boats were followed by the years on the sailing ship under Captain McDonald. The crew referred to him as the "bodach", the old man, as they would have to their own fathers. Often the crew would break into a Gaelic song as they worked.

On arriving in Dunedin, Robertson went to see Captain D. Cameron, the marine superintendent of the Union Steam Ship Company, looking for work. After three weeks waiting for work, "big, strong", energetic Robertson was up and away, taking several young men with him, heading for the gold fields first of Roxburgh and then of Alexandra; not for the gold, but to work on the gold dredges.

For an enterprising chief officer, who had spent the last 10 years working on steamships around the world, news of Charles Sew Hoy’s coal-fired steam-driven bucket dredges, developed back in 1889, would have been a sure drawcard to the river Clutha, with its Gaelic name for the River Clyde. Robertson’s work consisted largely of shifting the dredges, which involved dismantling, moving and then rebuilding them.

But Robertson was looking for another kind of gold as well. Eighteen months after arriving in Dunedin, and six months after shifting from Roxburgh up to Alexandra, he found his "Mrs Robertson". He and Martha Maria Herrell married on December 26, 1900, at her parents’ house, in "Spar Bush", Waianiwa, outside Invercargill. Charles Herrell, her father, was a labourer.

Martha herself was an officer in the Salvation Army, which meant that she had spent some years as a "soldier" serving in her home area, before training to become an "officer", the "equivalent of full-time clergy in other Christian denominations". This could lead to "church leadership, social programmes or management according to the person’s skills and experiences".

Such was the position this intelligent and enterprising young woman had reached at the age of 29. Robertson was 33.

With her at his side, a new set of gifts became apparent in Robertson.

As well as working on the gold dredges, he began in his spare time to collect money for the Salvation Army, to help newly widowed women and their children. That was just the beginning of his using various newspapers, including the Otago Daily Times, for starting funds.

One of the widows lived down in Ratanui in the Catlins. From 1904 to December 1905, he became a "home missionary" there (i.e. a lay preacher in a district where there was no minister), starting a fund large enough to build a church for the local settlers.

He preached all over Otago for eight or nine years. With the background of his father’s strong religious tendencies, and his own training as a chief officer in readiness towards a captain’s duties of spiritual care for his crew, this was not a huge step for him.

All this time poems of very different kinds were flowing out of Robertson: in Roxburgh, New Zealand For Ever!, the old Gaelic "battle incitement", calling troops away to the Boer War, which began in October 1899, and in Alexandra, Our New Water Scheme, a humorous, "silly rhyme" to greet the arrival of flowing water in Alexandra in 1903.

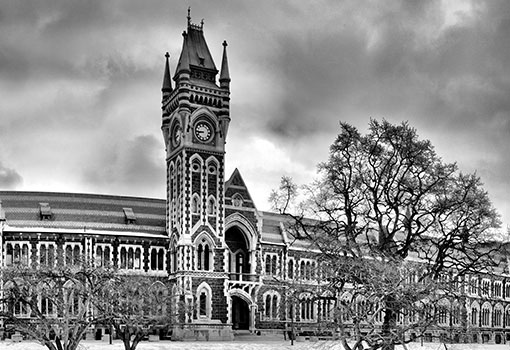

By 1905 Robertson and his wife and family (two of four sons born in Alexandra) had shifted to Belleknowes in Dunedin, and he was accepted as one of four bards in the Gaelic Society of New Zealand (established 1881 in Dunedin).

The executive, in its wisdom, saw the need for bards of different kinds:

- Neil McFadyen, probably representing the old Gaelic "village bard" tradition.

- Dougald Ferguson (no details given).

- Mrs Elizabeth Colville, writing in Scots and English (but no Gaelic) to hold the attention of the growing number of youngsters who had no Gaelic.

- Angus C. Robertson, composing in both Gaelic and English, the full range of types of poetry from local to political.

As was prophesied by an "elf" at his birth on Christmas morning 1867, somewhere towards 1910, the "dark clouds" were gathering in the blue sky. Both Robertson’s parents had died by then. He turned from preaching (for which he accepted no remuneration) to life assurance work, but his friends knew he was suffering "a nervous breakdown — again".

He was loved and respected in his home, in his most-loved society, the Gaelic Society, but also in the Burns Club and the Dunedin Pipe Band, as well as in his chosen city.

As can happen for an emigrant and refugee (then and now), when the new homeland has enfolded the exile, and everything is stable and safe, the harsh and terrifying experiences that drove them from their beloved land and people begin to make themselves felt and apparent.

Members of the Gaelic Society as a body were well aware of this human predicament, from their own background, in terms of battles, genocide, famine, the Clearances. The motto of the society was: "far am faigh an cograich baigh", in English: "where the stranger receives kindness". One of the "tasks" of the society was about being active socially in taking care of each other.

Robertson was aware of his own part in this as a true bard. He knew the people of the society and of the city of Dunedin. "The bard must speak to the hearts of men and women. He must cheer the sorrowing, uplift the fallen, soothe the afflicted and send the weary on their way rejoicing ... "

In 1913 Robertson undertook the long journey to the west coast of the United States. No doubt, the sea voyage was intended as much to ease his grief at his parents’ deaths as to assist his health. He called it a "lecture tour", to Spokane, Washington and Vancouver, Canada, but he also preached.

When he returned he continued working energetically as a life assurance agent by day. But at night, as was traditional for a bard, he was composing poems as well as studying Hebrew, Greek and Sanskrit late into the night.

In the end sleep deserted him, and "he, Aonghas mor laidir, big strong Angus, had a breakdown, with anxiety, stomach troubles and depression and pneumonia". He spent 10 years in Seacliff Mental Hospital, beginning "a few months" after the start of World War 1. He was 47 at this stage.

About halfway through 1915 his wife took their four boys down to Invercargill, to her parents. For Robertson in his grief, he "lost his wife and the children were scattered abroad". She trained as a teacher in order to be able to support herself and the boys (now 14, 12, 9 and 4). In 1921 she divorced him.

Fortunately for Robertson, Truby King was the medical superintendent of Seacliff Mental Hospital from 1889 till 1929, which included the years when Robertson was there. He turned what was effectively a "prison into an efficient working farm", and "prescribed" fresh air, exercise, good nutrition and productive work.

These years are likely to be the ones where Robertson described himself as a "gardener" in his autobiography.

At the same time, "Dr McKillop", who was on the Gaelic Society committee, was the doctor at Seacliff. For the year 1922-23 he held the position of chief and was therefore a "chieftain" in the following year, when Robertson left the hospital.

Sir George Fenwick, as the managing director of the Otago Daily Times and the Witness (from 1919 until he died in 1929), was able to help Robertson by giving him appropriate work at the ODT office. Fenwick was also an office holder in many welfare and cultural organisations, including the Patients and Prisoners Aid Society, which enabled him to assist Robertson in finding suitable accommodation.

From June 1925 "Bard Angus Cameron Robertson" was back singing Gaelic songs at the monthly concerts of the Gaelic Society.

Also in 1925, he published his poem Dunedin: The City Beautiful as a souvenir of the New Zealand and South Seas International Exhibition, held in Dunedin from November 17, 1925, until May 1, 1926.

By May 25, 1927, he had published his main collection of poems and prose, Salt Sea Tang. In his latter 20 years Robertson was busy writing away, adding new editions to his earlier books as he enlarged them, often with updates, as in his book Infantile Paralysis.

He died on September 11, 1945 aged 77. His simple gravestone is not far away in the Andersons Bay Cemetery, within earshot of the sea.

Catriona NicIomhair Parsons, a native Gaelic speaker of the Isle of Lewis and Gaelic professor in Nova Scotia, found A.C. Robertson’s book Salt Sea Tang while browsing in the now-closed Dunedin bookshop Scribes. She was adamant that Dunedin needed a plaque to Robertson in acknowledgement of the part that the Gaelic-speaking Highlanders played alongside the Lowland Scots in the founding of Dunedin and Otago.

A Writers’ Walk plaque to Angus Cameron Robertson will be unveiled in the Octagon at 10am on November 30.