Landfall Journal - This Green Corner Review

By Landfall Journal - Owen Marshall | Posted: Friday Jul 07, 2023

Owen Marshall Reviews The Deck by Fiona Farrell

This Green Corner (landfallreview.com)

Fiona Farrell is one of our foremost writers, accomplished in fiction, drama, poetry and essay, and as a scholar. All of these talents are necessarily employed in The Deck, her most challenging work yet, both for her and for readers. The Deck is a powerful and layered book, a cross-genre piece bringing together the past and the present, fact and fiction, poetry and statistics, escape and confrontation. Farrell never writes the same book twice and this is further proof of that.

Even the title itself has a teasing multiplicity of meaning. On receiving a copy of the book, I thought, what deck? After reading it, I was able to see various references and connotations: the decking on which the holidaymakers gather to tell stories, the deck from which life deals cards to us all, and of course, most significantly, the connection to the title of Giovanni Boccaccio’s classic volume The Decameron, which was written in fourteenth century Italy shortly after the horrors of the Black Death.

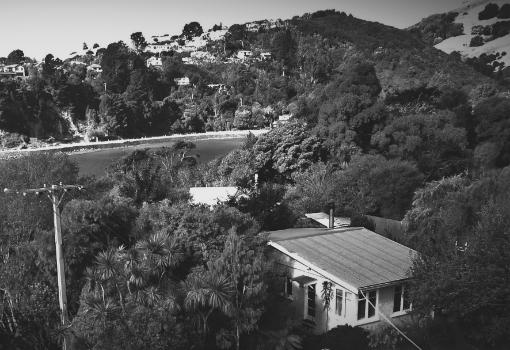

Farrell, too, is concerned with a devastating pestilence but also other threats in a world very different to Boccaccio’s: climate change, nuclear weapons, globalisation and a technologically enabled tsunami of information and disinformation. She is also vitally interested in human nature and relationships that remain essentially unchanged. In The Decameron, Boccaccio has seven young women and three young men flee to a villa outside Florence, where they shelter from the Black Death and tell stories unrelated to it as a distraction. Farrell also has her group of characters leave their city because of a pandemic and spend days at a rather large and impressive ‘bach’ overlooking the sea, where they interact, muse on life, and tell stories—activities that include sex, regret, apprehension, loss and poignant recollection. Ordinary people with names like Philippa, Tom, Pete, Baz and Maria come forward to reveal themselves in the stories they spin and the lives they have led. Again, as with Boccaccio, Farrell allows herself authorial comment on the work and the issues arising from it.

As is to be expected, her language is impressive in its originality and in its power. Descriptions of settings are both sharply imagistic and telling in their symbolism—for example: ‘There are macrocarpas on either side with enormous complicated trunks and cargoes of magpies gargling’; and ‘She holds the tiller steady as they hum along the base of the cliffs, leaving a long wake that made it look as if the bay were being unzipped and laid open.’ A bush walk is described in this way: ‘The track winds at a gentle incline uphill over tree roots and stones. Spiders have spun their webs across its width, long sticky threads that catch on their faces and snap one by one, so it’s as if they ascend by breaking one barrier, then another.’

She is equally evocative in the description of personality:

He’s one of those withered men, legs like dry kindling, polo shirt tucked into the waistband of knee-length shorts, hair scraped in damp strands over a pink scalp. Mainstay of the bowling club, Treasurer of the local branch of Rotary. A tidy man who amputates the branches from the trees on the boundary fence and mows his lawn with savage intent as if every blade might fight back. A man who has raised two terrorised kids and kept a lifetime grip on a dim, compliant wife.

One of the most memorable episodes in the book occurs on the fifth day of seclusion when a mysterious ketch is sighted in the bay. A yacht with no identification and no sign of activity. Three from the bach, Philippa, Ani and Zoe, go out to the vessel and Philippa climbs aboard to find horrific evidence of the pestilence they have been sheltering from:

The companionway is wide open, and from its mouth there is a breath that is at once sweet, like hyacinths or some heady spring flower, and sour too. Blue-vein cheese. Meat that has stood too long in the sun. Dog shit.

She breathes through her mouth and climbs down into the cabin. It’s filthy. Stained and crumpled, food scraps rotting in a pot, and the birds have been in, scavenging among plates and empty bottles. There’s sewage in the head and vomit on the floor. And in the forepeak, a tousled bed.

Two people are lying side by side and face to face. They are young. A young man in t-shirt and jeans, a young woman whose long blonde hair spreads over the pillow. Their legs are intertwined and her hand rests on his hip. And over them, over everything, the bed, the floor, a crimson lacquer of dried blood.

So it’s here. The organism, making its way to this green corner.

The structure of The Deck is complex and the language is dense, requiring an attentive reader. The authorial tone has a powerful and pervasive presence, and this gives an overarching unity to the book but also tends to overshadow and diminish somewhat the characters the novelist has created. At times the cuts from the past to the present, from story to story, character to character and fact to fiction become almost bewildering in their abrupt transitions, but even that suits a world depicted as on the brink of dissolution. Few writers would attempt a work of such apocalyptic ramification, archaic reference and genre-juggling, but Farrell’s ambition has succeeded in creating a memorable, relevant novel for our times.

In his Decameron, Boccaccio has a character say: ‘I suppose you all know, ladies, that a person’s sense and understanding consist, not only in remembering things past, or knowing the present, but that to be able, by both these means, to foresee what is to come.’ In times of great uncertainty and threat, knowing what lies ahead is both especially important and especially difficult. The plague created such a time for Boccaccio, while the pandemic has done the same for us.

The Deck, however, is more than a reprise of Boccaccio’s Decameron, more than a commentary on the onslaught of diseases such as Covid-19; it is also a reflection on the place of literature and culture generally in a world facing so many onslaughts. In both the initial section of the book, entitled ‘The Frame’, and in her conclusion, Farrell raises the question of whether works of fiction have any relevance to us now:

In this decade when the deliberate confusion of fact and fantasy is all-pervasive, what is the point of sitting in a room making things up? What can be the point of fiction, imagining an alternative reality, as the world outside the window is relentlessly destroying itself, one hamster, one fire, one war, one flood, one playground slide at a time?

The Deck is both a presentation of this question and a thoughtful, engaging attempt to answer it. The author has remarkable insight into human character and a mastery of language that allows that insight full expression. The best writing raises issues and emotions around our place in the world that remain with the reader long after the book has been closed, and that is the case with The Deck.

Fiona Farrell understands and reminds us that much of life is interpreted through narratives of one sort or another:

They sit on the deck looking down at a solitary boat, and in a split second each person invents an account of its origin and purpose for being there. Their accounts are based on their own experience of the world and their assumptions of what people might or might not do. Their scenarios pay heed to the state of the world and how it drives people to behave in certain ways determined by time and place. Their scenarios are formed in accordance with patterns learned long since in the deepest recesses of babyhood, of narrative sequence, consequence, and the operations of chance. They drink the last of the whisky, look down at the masthead light, that little lamp twinkling out in the bay, and they each, in that split second, make up a story.