“Will I walk again?”

By Brian Bourke | Corpus | Posted: Monday Dec 02, 2019

In the summer of 2005 I was visiting my sisters in my home town. After Mass a woman approached, put her arms around me and said, “Brian you are still alive. You were such a lovely boy”. My wife was standing nearby with a puzzled look on her face. It was not every day that strange women put their arms around her husband. That woman was Monica. Monica had nursed me one-on-one when I was fourteen and they thought I was going to die from polio. It was 49 years since Monica had last stood beside me. In 1956, Monica was twenty, and in charge of the isolation ward of the Ashburton hospital. I only ever saw her in a long white gown, rubber gloves and a white mask. She had beautiful blue eyes and wore rimless glasses. Her quiet voice encouraged me to eat and she held on to me when I went to the toilet. I needed her help to get sitting to standing, and because I could not stand she held me during the entire operation.

She was patient with me as the paralysis took hold and was never cross with me when I fell out of bed. I felt the comfort of her arm around me when I cried, and I cried often. In the middle of the night she would shine her torch on me and ask if I was all right. Did I need a drink? Time and again I asked her, “Will I ever be able to run again?” She replied quietly, “We will see, Brian.” Even in the early stages of having polio, I knew that nothing would be the same again. Monica’s reply told me so.

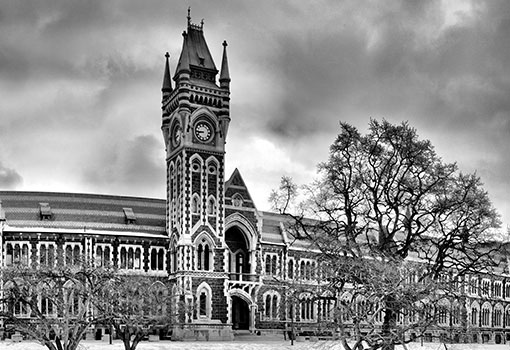

The isolation ward was quite separate from the other hospital buildings. Visitors were not allowed near us. They stood at the door, shouted encouragement and threw gifts to us. There were more than twenty people with polio and I was the only one who was paralysed. The ward was right next to the morgue and I remember seeing out of the window a man pushing a trolley draped in a white sheet. The building was next to the park and I could also look out on the vast green lawns of the Domain and see the white figures of men playing cricket. The contrast in the views from the different windows has remained fixed in my memory.

The isolation ward faced east and when the morning sun shone on my bed I was hot and the polio fever made it worse. The other people with polio were initially much worse than me. I was told they had a different strain of the disease, yet without exception they all recovered quickly and were discharged in three weeks. But I was partially paralysed, and had to stay all on my own. I can remember being very sad for the next week or so until they shifted me into the main hospital. That’s when I said good-bye to Monica.

It was exactly a month since I had been examined by the family doctor. He looked at my mother and nodded, and before long I was in his De Soto car on the way to hospital. In 1956 we all feared polio because it had a preference for children. There seemed to be nothing you could do to avoid it. The symptoms were like a very bad dose of the flu with a severe fever. The effects were life-changing. The paralysis was swift. We were utterly defenceless against it. Doctors had no answer. The newspapers spoke of so many victims, so many cases. It was an anonymous roll call of great unhappiness. Schools, picture theatres and swimming pools were closed. The others in my family were not allowed to go to work or attend school. Nobody came to visit them and they only went out to buy food. They sat around in the dreary nor-west heat of early 1956 and wondered if they could drink from the same cup or if they should wash all the dishes again.

When I arrived at hospital they were not sure if I had polio. They put me in a small room with green walls and no window to the outside. In the late afternoon they gave me a lumbar puncture and then left me alone. That’s when the paralysis started. I could feel it coming on. I had a strange feeling in my left arm and my left leg. The nurses did not come to check on me. I got out of bed and walked up and down that small room until I could not walk anymore and collapsed on the floor. I fell asleep and woke as I was being lifted back into bed. I heard the familiar voices of my Mum and Dad talking with the doctor outside the door. They were discussing putting me in an iron lung if things got worse. The next morning I was shifted to the isolation ward. When I arrived there I was greeted by my five-year-old brother who also had polio. “Hi Brinny, are you here too?” he said.

When I was moved to the main hospital they started the treatment: hot packs every three hours, and being put in a bath and made to exercise. Salt was added to the water to make it more buoyant. That was the entire treatment. My mobility now relied on an ancient wooden wheelchair. In the ward with me were a lot of old men. I say old, but they probably just seemed old to a fourteen-year-old. I was put in a bed next to a man called Peter who was a bit younger than the rest and a paraplegic. He had been in hospital for five years when I arrived. He was engaged to be married when he had an accident. His fiancée was still coming to visit him almost every day. She sat on the end of his bed and they spoke quietly to each other. They never touched. They never kissed. She was a Salvation Amy girl and she sometimes came in uniform, including the black bonnet. Peter often talked about her. He told me that one day they would marry. She sometimes spoke to me. She asked about my family. She thought she had met one of my brothers. But one day the fiancée stopped coming. And as the days turned to weeks Peter was overcome by sadness. He was a big man and when he cried his whole bed seemed to shake. It wasn’t till many years later that I thought perhaps she saw the talkative fourteen-year-old as her ticket to freedom. She knew that Peter enjoyed my company and her departure would be that much more bearable for Peter with the distractions I could provide.

A year after I left hospital, I was walking with a steel calliper on my left leg, and a walking stick. I went to visit Peter and found he had been shifted to a private room. Before I went to his room the nurses told me Peter had lost his eyesight. He greeted me with a cheery “hello Brian” but his deterioration was plain to see. He was in a strange bed that sandwiched him between two boards. He told me with a smile that was to make it easier to turn him so they could wash both sides. I went with my mother to Peter’s funeral a month later and as we stood around the graveside I noticed a young woman in a black bonnet with tears in her eyes. The minister competed with a stiff nor’wester as he stood at the head of the grave and read the committal, and a group of Salvation Army bandsmen struggled against the wind to play “Abide with Me”. I had been an alter boy and attended many Requiems but this was my first funeral as a mourner. I had spent six months in a bed next to Peter in a ward with many people at the end of their lives, and I saw death, dying and grieving right up close. I got to know that if an old man had more than three visitors then the end was near. The screens around the bed would be closed. I could see the shadows of those gathered, I could see them hug each other. I could hear the soft voices and the sobbing. The vases of flowers that seemed to be everywhere did not help the sadness. The nurses were nowhere to be seen. This is the time when families were to be left alone. Those were the days when some people went to hospital to die. My Mum and Dad were very angry about this and tried to have me shifted to the children’s ward. But this was not allowed, and I was left to make friends with men five times my age.

The old men talked to me and told me their life adventures. I was a good listener. There were men from WW1 and one man from the Boer war. They told me stories about the wars. I learned that in the Boer war you did not go out in the open as the Boer snipers would shoot you from 800 yards away. It was here I learned about the birds and the bees. There was a row of seven beds on a balcony. My bed was in the middle. I learned that grown men talked about sex a lot and it didn’t seem to matter how sick they were. My first inkling about this thing called sex was that the men laughed when they talked about it. They spoke freely about their conquests and went into some detail; each one trying to outdo the other. This was the first time in my life when I had heard the topic of sex discussed openly by adults. I was an innocent, having been educated by nuns to the age of thirteen. Of course I wanted to know more about the subject that seemed to make adults laugh. As you grow older you realise that sex is a very funny subject. But I digress. I never asked questions. I just listened. But I worried: was it a sin to listen to such talk?

After two months I was enrolled with the correspondence school but the distraction of the ward’s routines made it difficult for me. Without a teacher or kids of my own age around me, I was lost. I sent one of the green bags back to the correspondence school stuffed with blank paper. I was angry and bewildered. One of the distractions was Clarky, a man in his nineties, who would shuffle by my bed each day and sit on a chair. He would look both ways and say “Where is the bloody coach? That driver is never on time.” And he would motion to pull a pocket watch from a waistcoat and then declare “He is always late, I will walk”. As he walked away little marbles of poo would fall out of the legs of his pyjamas. There were other distractions, and with the mobility of a wheelchair I was able to explore other parts of the hospital. That’s when I met Dawn, my very first girlfriend. Dawn was in the children’s ward and was also wheelchair-bound. We used to meet in the corridor and hold hands and talk about our illnesses. Those hand-holds were my very first attempt at contact with the opposite sex. She would take my hand and put it on her thigh. She was a little more advanced than I was.

After three months I was allowed out of hospital for a few hours and my mother would come and take me in a wheelchair to the park to watch the children from my school play rugby. Although I wanted to leave the hospital I was very self conscious about being in a wheelchair and no matter where my mother pushed me or parked me I was never satisfied. I hated it when my classmates came to talk to me and looked down on me. All I wanted to do was to go back to the hospital. The truth was I had seen my friends playing games which would be beyond me. I was unhappy. I was very ungrateful for what my mother did for me. God Mum, I wish you were around now so I could say sorry.

I eventually had a full length calliper made for my left leg and on one of my days out of hospital I had a go at riding a bike. I succeeded and this enabled me to leave hospital because I could bike to the hospital for physiotherapy. I did this every day for a year. The treatment was useless. My return to school was very difficult because I had gone from being a fast runner and a rep rugby player to getting along with a stiff leg and a walking stick. Even at that stage there were children who would not come near me for fear of catching polio. I fell over many times and was helped up by my classmates. I was very self-conscious and regarded falls as failures. And I still do.

I was in a class of mostly girls. Thanks to the old men I was miles ahead of them when it came to the birds and bees stuff. But I was still terrified if they came close or spoke to me. What if I was hair trigger or got a stiffy like the old men had talked about? I went to the school dances but did not dance, I just watched. The girls wore blouses and lipstick and full colourful skirts. They smelt nice. When I got home I would cry because I could not dance.

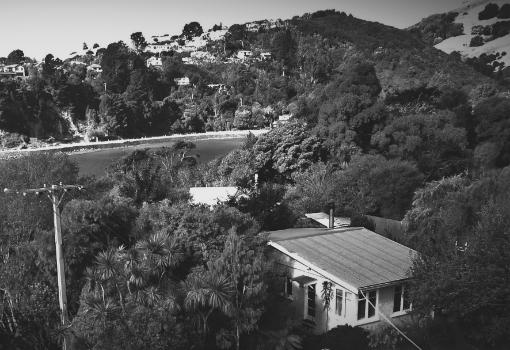

That first summer after polio I went swimming on my own in the braided streams of the Ashburton River. I would take off my calliper and get into the water and be washed downstream as I could not swim against the current. In the shallows I would make my way to the side and crawl back to where I left my calliper. I went through this routine several times as I would not go to the public swimming pool because people might see my skinny leg.

Fast forward twenty-five years. One of the features of polio in some people is that they must continually challenge their physical ability. One day one of my friends asked if I would like to climb Mount Holdsworth, a mountain 4800 ft high west of Masterton. I said that would be fun to do. To get fit for the climb I went swimming. Well, I went on that climb, and for the next twenty years I walked all over the Tararua Ranges. I went with the same people each time. One of the people in the group, Peter, walked in front of me every step of the way to protect me if I fell. They were all unbelievably kind to me and took me to places in the Tararuas that many ordinary trampers have never visited. We were known as The Old Crocks and our efforts are mentioned in the book “Story of the Tararuas”. I have since climbed Mount Holdsworth nine times.

I also carried on swimming, and swimming has taken me to other parts of New Zealand and other parts of the world. I now don’t care what I look like. Believe me there are people with worse bodies than mine. I completed a six km swim in the Atlantic off Copacabana beach. I have swum the length of Lake Taupo – 40.1 km – in a relay with 5 others. I have done that twice. I have swum the length of Tauranga Harbour four times. I have done three across-harbour swims in Wellington. My efforts are more modest these days and I compete regularly in Master Swim meets, never with much distinction. But it keeps me from going to seed and I am proud to say that up to a couple of months ago I could still swim 50m butterfly.

Polio took away the use of my left leg and weakened my left arm. I have had a walking stick and a prosthesis of various sorts on my left leg since I was fourteen. I have some minor residual problems with my waterworks and I always wear specially made shoes. If I have an anaesthetic or strong pain relief I am completely ga-ga for four or five days. This is one of the non-physical effects of polio and the literature suggests it is because of polio’s original attack on the nervous system. Alcohol was my nemesis and I had to give it away completely. I have been told to be very careful not to break my left leg because it is shrinking and going chalky. If it breaks it is unlikely to mend. On the plus side I only have to cut my toenails every five months.

Other than that I am fine. I’ve had a successful marriage and business career as a chartered accountant which put bread on my table. By far the worst thing for me is the cold. And as I grow older it gets worse. In winter I shower at night and jump straight into bed. After morning showers I lost too much body heat. But battery technology has improved and I now have battery-heated socks. To say these socks are life changing is an understatement. For me it is the same as putting a man on the moon. I can go outside in winter for as long as I like and do anything I like. I put them on in April and take them off in October. Wonderful!!

Many years have passed since that horrible epidemic. Thankfully my education has broadened. I cannot boast about what I learned behind the school bike sheds. But what I can say is that I never met anyone who had teachers like me. The old men, the nurses, Sister Timms. When I returned to school I was well behind in English and Maths but way ahead in knowing what grief and sadness was like. You don’t have to be part of the sadness to feel the sadness. I also knew that death was real. And when adults cried they cried quietly and for long periods. It is not a weakness to ask for help.

Plus, my knowledge about the birds and the bees was such that it would be years before my schoolmates caught up.

P.S. My five-year-old brother made full recovery.

And oh yes – Monica still has beautiful blue eyes.