Poetry Shelf review: Fiona Farrell’s The Deck

By Poetry Shelf - Paula Green | Posted: Friday Jul 21, 2023

The novelist is about to step out onto the unknown ground that is every new book. She will make up characters and a setting and a plot and walk about in the imaginary land that always lies just offshore, alongside reality.

Poetry Shelf review: Fiona Farrell’s The Deck | NZ Poetry Shelf

She has no idea if her story will work. It's always a bit of a gamble. Maybe making things up will feel ridiculous, irrelevant before the online deluge of fact. Maybe she'll lose her nerve. Maybe her imagination will fail her, her characters will dwindle to dots. Maybe she will be be unable to settle to the daily grind at the computer, distracted by the news reports and their insistence on failure, collapse, shambles.

from 'The Frame'

Fiona Farrell's writing has enthralled and inspired me from the moment I fell into the freshness and delight of The Skinny Louise Book in 1992. Since then I have devoured her poetry, her novels and her nonfiction. Her writing prompted by the Christchurch earthquakes was humane, lyrical, layered and so utterly necessary. When I think of Fiona's writing, I am reminded of the power of books, regardless of style or genre, to move us, nourish us, to challenge without ever losing touch with both heart and mind.

I recently read an essay in The New Yorker by a disgruntled critic who poured a wet blanket over our contemporary enchantment with and cravings for stories and storytelling. We are besotted with story. And yes, a story might not have the power to dismantle global warming or feed the hungry or put an end to violence, yet stories have mattered and continue to matter. It matters that the awkward child picks up the picture book and sees an awkward child dressing in a sparkling dress or singing out of key or kicking a football through a hoop. Or reading a book in a nest for an elephlion. It matters that I read stories that entertain me, lift me out of despair and maybe signal choices for the good of the planet. It matters that I can step into other points of view, close to mine, or at arm's length. As the film-directors, the Tavianni brothers exclaimed when they first saw themselves and their stories reflected on the Italian cinema screen: 'Cinema or death!' We tell stories from the moment we get out of bed; to ourselves, to each other, to our friends, family, doctors, politicians, to strangers. Some of us crave to write. We might be plagued with doubt over sending our books in to the world and what difference that book will make. But stories represent how, where, who and why we are - and how, where, who and why we will or might be.

Fiona Farrell's new novel, The Deck has made a difference to me.

The Deck steps off from Covid, borrowing the structure and motifs of Boccaccio's The Decameron from the 14th century to re-present a novel that speaks from and to our contemporary plague. Boccaccio sets his novel, his sequence of stories and homage to the reach of storytelling, in the time of the plague in Florence. He opens with 'La cornice' (The frame), an autobiographical and nonfiction introduction to the scene and the situation. Fiona follows suit. I am catapulted body and heart to our time of Covid, to the new language that introduced bubbles and isolation, RAT testing and quarantine hotels, border controls and conspiracy theories, masks and hand sanitisers, the 1pm news gatherings and the daily statistics, teddy bears on fences and deserted city streets, online ordering and the stockpiling of flour and toilet paper.

For me, Fiona nails the uncertainty, the unreality and complexity of the situation, the daily reassessments and difficult choices, the willingness to work together for the good of the whole, the unwillingness by some to relinquish individual freedoms. The reevaluation of what mattered.

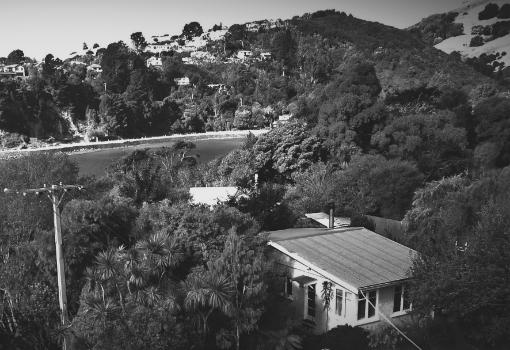

The Deck. When it looks like the country is about to collapse under another plague, Philippa makes a beeline for her beach house with her husband Tom and some friends. The retreat feels like a mini intermission, a temporary retreat from living in the thick of the plague, its consequences and the tough decisions. As in The Decameron, the group of friends pass the time drinking, eating, telling stories. So what stories get shared on the brink of catastrophe? In the frame story, Fiona speaks as the novelist, and asks what the point of writing fiction or a novel is, when the world is under multiple threats. She asks: 'Is fiction no more than a brief solace, a distraction on our the way to our own extinction?'

On the third night, the friends debate China v America, war and famine issues, and then meander through best books, best movies (yes The Bicycle Thief!), places to visit, sports, philosophy. Each person takes a turn at spinning a yarn, drawing upon their own life, hinting at dark undercurrents, turning points, mis-turning points, yearnings. At times the story is a gut a punch to the listener, a secret revealed in public. Each story is headed by the epigraph: 'A tale of one who, after divers misadventures, at last attains a goal of unexpected felicity.'

Ah. This is a book to read for yourself, to track and trace the impact on your own heart and mind as you are transported back to 2020 and the arrival of Covid, and into your own cache of stories, secrets and intimacies, your misadventures and felicities. I am struck by how we perceive things, how the protests at parliament were a sword in our side, when decades ago, the anti-Apartheid and Vietnam protests attracted so many more protestors. Ah. And how the image of the desecrated children's slide at Parliament was so unfathomable. What on earth does this rebellious act stand for?

I am at the novel's ending. I love the novel's ending. I am transported back to the endings of post-war Italian neorealist films. I am there watching (think The Bicycle Thief and Rome, Open City) as the characters and a group of children walk down the road, down the road to the final frame, to the word HOPE, and even though I am wrung out and smashed to smithereens by planetary greed, I am strengthened by a collective impulse to write - as resistance, as solace, as illumination. There are multiple versions of who we are and there are multiple versions of who we might be. We need novels. We need stories. We need imagination and we need the mirror held up.

Fiona Farrell's new novel, The Deck has made a difference to me.

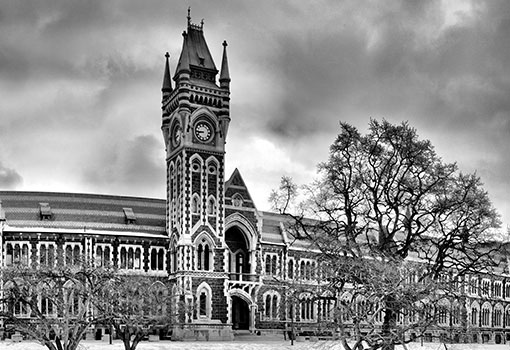

Fiona Farrell, born in Oamaru, was educated at the universities of Otago and Toronto, and has published volumes of poetry, collections of short stories, non-fiction works, and many novels. Her first novel, The Skinny Louie Book, won the 1993 New Zealand Book Award for fiction. Other novels, poetry and non-fiction books have been shortlisted for the Montana and New Zealand Post Book Awards with four novels also nominated for the International Dublin IMPAC Award. In 2007 she received the Prime Minister’s Award for Fiction, and in 2012 was appointed an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to literature. The Broken Book, a book of essays relating to the Christchurch earthquakes, was shortlisted for the non-fiction award in the 2012 Book Awards and critically greeted as the ‘first major artwork’ to emerge from the event. Her work has been published around the world, including in the US, France and the UK.