The Flick - Theatre Review

By Terry MacTavish | Posted: Saturday Jul 06, 2019

Significant Issues Smuggled in under the Seemingly Innocuous Dialogue

THE FLICK

By Annie Baker

Directed by Lara Macgregor

Presented by Wow! Productions

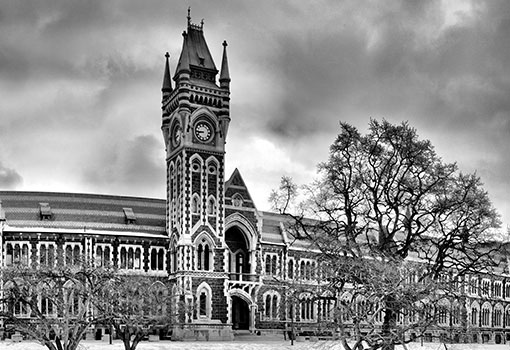

at Allen Hall Theatre, University of Otago, Dunedin

Until 20 Jul 2019

[2 hrs 40 mins incl. interval]

Reviewed by Terry MacTavish, 6 Jul 2019

There is a powerful, irresistible aroma of buttered popcorn. In the friendly dark around me shadowy forms murmur and rustle their way into paper bags of assorted sweets, a jaffa is rolled down the stairs and someone giggles. A burst of wonderfully evocative music rising to a stirring crescendo takes me back instantly to the movie theatres of my childhood. Surely any moment a newsreel will flash onto the screen, bor-ing, then a cartoon, hurrah, then the main feature. Doris Day if I’m lucky, John Wayne if I’m not.

But the lights spring up and we are the screen, facing rows of seats, bare but for the detritus of the movie patrons: empty bags, discarded food, the odd shoe, and spilt popcorn. Lots of popcorn. The picture show is over and we will spend the next two or three hours* in the intimate company of the ushers, vendors and cleaners of the theatre. All two of them, the old hand Sam and the newbie Avery. And Rose the projectionist, for this is an old-fashioned cinema that has not yet gone digital.

The Flick caused some controversy when it opened in 2013, before going on to win the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Patrons of its first productions walked out because, presumably, it was too much like real life. It was anti-theatre. But this is of course the brilliance of Annie Baker. Legend has it that early audiences at the play by Russian genius Chekhov said not, “I am going to the theatre to see Three Sisters,” but “I am going to spend an evening at the Prozorovs.” Similarly by the end of this evening, we will feel we have been sweeping up that popcorn forever, beneath the immaculately realistic projection box, part of the crew, part of a true experience.

WOW has mounted a thoroughly professional production. For those wondering where the Fortune has gone, well, some of its very capable staff have moved on to give The Flick its slick feel: Anna van den Bosch smoothly operating Martyn Roberts’ ingenious lighting scheme; Mark McEntyre’s set design solidly executed by Peter King with Matt Wilson; versatile Katrina Chandra and Rosella Hart on the production side; and of course, shining her light over all, erstwhile artistic director, the luminous Lara Macgregor.

As director of The Flick, Macgregor has ensured her talented cast avoid the appearance of ‘acting’. Baker’s extraordinarily naturalistic dialogue demands a minimalist approach, and above all, respect for those awkward silences that make up conversation in real life. Aha, Pinter, you are thinking, but for a contemporary audience, with shared knowledge of Pulp Fiction rather than Sidcup, Pinter can seem remote and even quaint compared to Baker.

Baker’s world, a run-down cinema in Massachusetts staffed by misfits, is less threatening than Pinter’s, but more hopeless. These people are failures, in menial jobs with no prospects, wages so low they live with parents and daily confront the ethical dilemma of fleecing their incompetent employer of ‘dinner money’ in a pitiful little scam passed on to each new employee. Ironically, considering how utterly believable they all are, they accuse themselves and each other of being fake, being stereotypes, acting like they are in a sit-com. Has their generation lost the ability to be real?

The acting for what is actually super-realism has to be tightly controlled, and Macgregor’s fine cast – including Thomas Makinson in a cameo role – give wonderfully restrained performances. Nick Dunbar is utterly convincing as laconic Sam, the oldest and hence most dispirited, with his not-so-secret yen for Rose and hopeless aspiration to be trained as a projectionist, the only tiny upward step possible. With energy-efficient slouch and baseball cap pulled low over deadpan face, he can make even wringing out a mop an act of aggression. Yet he is incredibly moving in his long confessional speech, delivered to the audience as he is unable to meet the eyes of the person he is addressing.

His laid-back patronising of the new recruit, Afro-American Avery, gradually warms to something approaching admiration, as they find common ground in the six degrees of separation game applied to movies. Avery is hard to stump, a film snob who has seen everything and mourns the death of real film “which can express things computers never can…it’s like looking at a postcard of Mona Lisa instead of looking at Mona Lisa.”

The audience sympathises audibly with Timothy Itayi, charmingly earnest as Avery, as he agonises over the scam, partly on moral grounds but more because should they be caught, experience teaches him that as a black man he will be the one to get the blame. Beneath his calm exterior, his courteous resistance to Rose’s provocation and Sam’s challenges, Itayi allows us to sense the volcano beneath. The mighty biblical passage Ezekiel 25.17 (by way of Pulp Fiction) gives Itayi his impressive bravura moment, and he raises the rafters all right.

Sam Shannon’s Rose is the liveliest character, with a naughty sense of humour and propensity for teasing the hapless males hiding her fear of commitment. Her hair dyed a bold green, Shannon is enchanting in the role. Her particular show-stopper is a fantastic dance number when she rips right round and through the rows of seats shaking it out to ‘Hey Ya’ by Outcast. A set composed of rows of raked seating might seem restrictive but Macgregor utilises it throughout, sometimes literally, as a springboard for imaginative action, and Shannon’s explosive moves are the ultimate test, triumphantly successful.

Gradually we are absorbed into their quiet groundhog world as with each new scene the popcorn is back to be swept up once more, witnessing their subtle power struggles, sharing Rose’s astrological charts, Avery’s bizarre dreams, and Sam’s reluctant trip to attend his ’retarded’ brother’s wedding. Their clumsy interactions are excruciating but funny, and a reminder that simple friendship can be what makes life bearable.

What is surprising is not how painfully amusing banal language is, nor even the anything-but-banal quirks of the trio (vomit-inducing shit-phobia? really?), but how many issues of significance and depth are smuggled in under the seemingly innocuous dialogue, until we find ourselves facing the ultimate existential question, “Who is the righteous man?”

Like many in the audience, I am excited WOW has given us this chance of seeing a work by an extraordinary, feted writer. The Flick does not disappoint. Because it all unfolds in real time it is necessary to relax and adjust to the rhythms, but with Baker’s subtle script in the hands of these experts I don’t want to miss a word. Or a pause.

There is an absolute luxury in surrendering to this “mining the minutiae” of ordinary lives. I know these people. I care about what happens to them. I can’t bear to see them to let themselves down. And the ending, resolving the tension achieved by a fearless coup de theatre, does leave us with a little hope. Compared to say, Eleanor Rigby, it is almost uplifting.

I understand why some in the audience are planning to come again to this truly rewarding production. I liked the free popcorn too.