A town trod by Poets: The search for truth on Dunedin streets

By Roger Hickin | Posted: Monday Jan 09, 2017

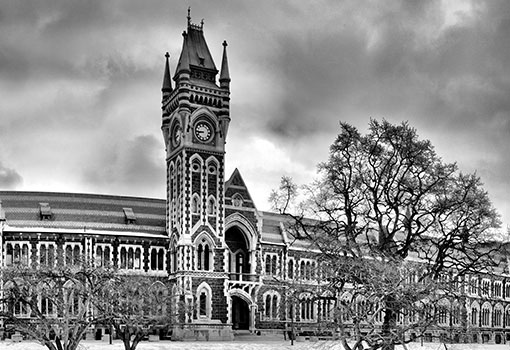

A paper by Roger Hickin delivered at the University of Otago Centre for the Book 2016 Symposium: Book and Place

Dunedin Poem, Dunedin Walk, Dunedin Story . . . so Janet Frame titles three of the poems in THE POCKET MIRROR, a collection mostly written in Dunedin around the time she held the 1965 Burns Fellowship. James K Baxter’s COLLECTED POEMS lists Dunedin Habits, Dunedin Morning, Dunedin Revisited. Excluding environs, in YOU FIT THE DESCRIPTION, the selected poems of Peter Olds, there are at least 25 poems specifically located within the city; the Baxter collected has 20 or more; THE POCKET MIRROR 18.

Beginning with Thomas Bracken in the 19th century

watch[ing] the golden shower

Of yellow beams, that darted

From the sinking king of day,

And bathèd in a mellow flood

Dunedin from the Bay . . .

as the editors of UNDER FLAGSTAFF, a 2004 anthology of Dunedin poetry, state in their introduction: “Of all New Zealand’s cities, Dunedin seems to have evoked more poetry than any other.”

1. Dunedin as “a setting for something to take place in”

Back in Dunedin this spring

I walk down narrow Bath Street

old route to the public bar

door of the European Hotel

last of the counter lunches

and long afternoon sessions

So begins one of my own poems, Revenant. Dunedin was the locus of my misspent youth, not all of which I care to remember. A backdrop, to paraphrase Iain Lonie, whose Dunedin was an antipodean Mt Purgatory, a backdrop to the adventure of suffering . . . “hill tree and tower / by sunlight or starlight assembled into a setting / for something to take place in . . .”

Dunedin is the setting for much of the poetry of Peter Olds. Many of his Dunedin poems are stories of, footnotes to, his walks, “[s]treet after salt-wind street”. “The compact between writing & walking is almost as old as literature–– a walk is only a step away from a story,” says Robert Macfarlane in THE OLD WAYS, A Journey on Foot.

Olds’s selected poems from 2014, YOU FIT THE DESCRIPTION, opens with a previously unpublished early poem, Christmas Day at Joe Tui’s, & the young poet “Walking stoned through the university grounds, barefoot, / in need of a wash, in need of a change of clothes––”. “Crossing Cumberland Street to the dark green museum // reserve”, he writes, “I don’t care about my dirty state, for I have counted / on Joe, the Chinese fish and chip shop owner, to be sane // enough to have left his door open for the Infidels who / have missed out on the Holy Dinner.” The Mecca of this brief pilgimmage arrived at, in the “big white steam rising from the / entrance of his greasy door”, Joe’s “own stoned face” joins the poet’s “in a blissful, telepathic grin”. Some walks are a step towards illumination. Some have a grimmer cast. In A yearning for specific pinetrees, subtitled Small pictures of Dunedin, from 1978, Olds writes:

Tonight, walking home

hunched and greasy from chips and beer,

old dreams rose and grumbled behind me.

I ran the last block in fear.

Pausing on the steps near home

I saw the victorious moon rise beyond

dark North East Valley:

The sky clear, cool and pale.

Earth black from long afternoon rains.

And a 2008 poem, Belleknowes park finds him stepping into a story, this time in the imagined company of some literary forebears & an ex-lover, walking up

Highgate towards the Town Belt,

a nor’west wind at my back.

Stopped at Belleknowes Park

for a pee in a clump of bush;

got sniffed out by a black dog.

Took a seat on an antiquated

bench to take in the view ––

the ground hollowed at my feet

by those who’d been before me

watching the surf roll in to St Clair.

Poets, Charles and Ruth

comparing peninsular visions;

A.H. and James K. sharing

egg and parsley sandwiches,

young couples just starting out

on life’s moonlit journey . . .

I lived round these parts once

in a house with roses and a woman.

On quiet nights you could hear

the sea smash its guts out

on the beach below.

We drank too much wine,

stopped thinking of each other.

One night in heavy snow

she kicked me out, and –– not sure

whether I knew I was coming

or going –– I went by this place

believing I wouldn’t be back.

In Dunedin Poem, wondering “Soon will the days be dark? Will the mists come, / the rain blow from Signal Hill down Northeast Valley / that in winter lies in shadow”, Janet Frame climbs aboard a trolley bus & travels “to where / down a long street lined with flowering cherry trees I walked / nineteen years ago / to stare at the waves on St Clair beach.”

Charles Brasch, a keen walker who titled one of his books AMBULANDO, intones a mantra of Dunedin street names in one of the late poems from from his posthumously published collection HOME GROUND: “Great King, Filleul, London, Albany Steps”. He tramps his “streets into recognition” & listens at dawn “for the low sea / Wind-scourged, sullenly heaving / Sounding where every street ends”. For him Dunedin is a city that “Floats on the void edge. Past the sentry beat / Of breakers, beyond White Island, last step into nothing”.

In EARTHLY: SONNETS FOR

CARLOS, Ian Wedde, 1972 Burns Fellow & postman (once the default poets’ occupation), tramps the hill suburbs where “White

hoarfrost like an old man’s stubble / coarsens the gaunt pavements of Halfway

Bush”. (Baxter, another ex-postie, has “Frost standing up like stubble in the

streets / below the knees of Maori Hill”.)

Always alert to terrestrial paradisos,

Wedde spots how “Dozens of wrangling sparrows have built their / shitty serviceable nests high up Three / Mile

Hill in a power transformer” where “every day unscorched & lusty . . .

they’re getting on with it in that airy / crass penthouse with its fine view of

the sea”. Unlike Bill Sewell, who wonders of Dunedin: “How can anyone be at home / on the edge of the world?”

Wedde, like Cilla McQueen & Ruth Dallas, has also written many fine Otago Harbour poems, which alas fall beyond the scope of this paper.

2. Dunedin as “a cradle of virtue” ––question mark

“Those whiskered bigots who planned / this city in holy ignorance of its terrain / meant it a cradle of virtue” writes in Iain Lonie in The Entrance to Purgatory. But James K Baxter asks the stuffy university authorities in A Small Ode on Mixed Flatting: “Have you forgotten that your city / Was founded well in bastardry / And half your elders (God be thankit) / Were born the wrong side of the blanket?” “If there is any culture here” he says in On Possessing the Burns Fellowship 1966, “It comes from the black south wind / Howling above the factories / A handsbreadth from Antarctica, // Whatever the architect and planner / Least understand.”

Janet Frame’s Dunedin is a city that “takes no chances”. On Sunday afternoons, “Having been to church the people are good, quiet, / with sober drips at the end of their cold Dunedin noses”. “It’s no surprighs / [she writes to Frank Sargeson] to find Dunedin has no thighs / that all is cold loin of mutton / beneath the belly button.” Even the wind is complicit in the city’s respectability, combing “the sea gulls, like dandruff, out of the sky”. In Cat Spring, however, feline “alley-hunger makes a sexual slum / of a city that is rumoured to be clean”, while in Dunedin Morning the Leith Stream “always a loud grumbler / after a feed of high-country rain / . . . cannot keep its wide apron clean”.

In PIG ISLAND LETTERS, Baxter calls Dunedin “Calvin’s town”, & in A Small Ode on Mixed Flatting “King Calvin in his grave will smile / To know we know that man is vile; / But Robert Burns, that sad old rip / From whom I got my Fellowship / Will grunt upon his rain-washed stone / Above the empty Octagon, / And say–– ‘O that I had the strength / To slip yon lassie half a length!” In The Man on the Horse, that Dunedin-infused book of essays from 1967, Baxter writes:

“Twenty years ago, as an ineducable dry-throated student walking the streets of Dunedin, making good and bad poems and fighting like a ferret against whatever seemed likely to paralyse me, I would often look to the statue of Burns, with his back to the big cathedral and his face to the Oban Hotel, for approval and consolation. Later I mentioned the same statue in a short story:

‘At noon I walked down the sixty-eight steps at the back of the Town Hall. The town knew me, the heir to Adam’s lost fortune whom the lawyers had given up hope of finding; and I knew the town. It opened its brass-buttoned coat for me to hide inside. Robert Burns, two hundred years dry on his tree stump above the Octagon, waited for the traffic to stop so that he could step down to the Oban Hotel, bang on the bar and order a bucket of gin and Harpic . . . But the clock struck twelve, scattering pigeons over the sun-roofed town.They roosted again on Robert Burns, clucking and dropping their dung on his ploughman’s collar . . .’ ”

In the mid-seventies, not in good shape, Peter Olds knows he must escape “up past the Robert Burns statue / (himself stiff-grey with crazy), / up the long steep highway / to that building at Halfway Bush . . .” to “meet the god of Clinic” & “get cleaned up”. Robbie Burns himself is not so lucky. In Blues for Robbie Burns, during the unveiling of a Writers’ Walk plaque, feeling depressed, “this crazy mixed-up statue who has never had a bonk / on the back seat of a Toyota Corolla / or eaten gateau with a fork & spoon / or been invited to a chardonnay shindig at the poncy / Art Gallery across the road . . . steps gingerly down from his tree-stump seat / & begins to make his wobbly way across the street / to the Methodist Mission coffee lounge for a bowl / of homemade soup / & is hit by a taxi & killed instantly . . .”

Nearby Brighton may have been the centre of Baxter’s poetic universe, but Dunedin was the town he ventured into when he first came of age, the hub of despondency & illumination (to borrow Vincent O’Sullivan’s choice juxtaposition), the town he returned to in the mid-sixties to take up the Burns Fellowship.

In The Cold Hub he remembers an adolescent dark night of the soul, “Lying awake on a bench in the town belt, / Alone, eighteen, more or less alive, / Lying awake to the sound of clocks, / The railway clock, the Town Hall clock, / And the Varsity clock, genteel, exact / As a Presbyterian conscience”.

In Words to Lay a Strong

Ghost, his re-working of Catullus, the aging poet returns to a scene of

youthful sexual misadventure: “They’ve bricked up the arch, Pyrrha, / That used

to lead into / Your flat on Castle Street––Lord, how / I’d pound the kerb for

hours, // Turning this way and that / Outside it, like a hooked fish / Wanting

the bait but not the barb”.

In

The Muse, a

1966 poem addressed to Louis Johnson, Baxter sips tonic water in the Shamrock

bar of what I think is now the Clarendon Hotel, & watches his alter ego, “a

drunk with unlaced shoe . . . [make]

exit up Maclaggan Street” to where his woman, suffering “the clouting winter of

the town”, awaits him “on a foul green-painted balcony”. “I think / Johnson,”

he comments, “it was the Muse, whom you and I / Unhinge by our civility.”

On the one hand Baxter’s Dunedin is a mausoleum of bourgeois

respectability, on the other a theatre of Bohemian revolt. And at its centre is

the Leith Stream, symbol for Baxter, despite its culverted course, of the

natural forces repressed by the Calvinism of the times.

In Henley Pub (a traveller’s

soliloquy) the traveller’s mistress has a flat in Royal Terrace (one of the

terraces of Purgatory perhaps) “open to the Leith Stream’s roar” (which is a

bit of a stretch!) and a wet tom-kitten (perhaps a descendant of one of Frame’s

alley-hungry lot) squealing at the door. Later, in A Letter to Peter Olds, from upcountry on another river, the

Whanganui, having gone north “like a

slanting rainstorm”, Baxter

encourages the younger poet to “Have a wank for me, on the grass beside the

Varsity, / I mean at that old place, between the Gothic turrets / And the

waters of the Leith.”

Olds himself lived for a time in the early ’70s on the banks of “the Leith’s hard stream” in “respectable montgomery avenue”. In Revisiting V8 nostalgia he roars off down it in a ’54 V8 “beer bottles / rolling in the back, fumes pouring up thru / the floorboards”. It is in Montgomery Avenue where “the woman who once lit [his] mind” leaves her habits behind. But a recent poem has

Junkies in wrecking machines

loose on Montgomery Avenue.

. . . .

A ghost of a cat––a black cat––[poking]

its head above the rubble,

over the edge of a still intact

section of wall, above

where a mattress once lay

on a floor beside a cranky radio

& a cold cup of untouched tea

The ghost-cat advises the poet: “Old man, / go & listen to the Leith”.

3. Dunedin as “a place to go on from”

. . . to borrow another phrase from Iain Lonie’s poem.

Peter Olds’s Taking my jacket for a walk on the hill suburbs of Dunedin––a poem from a forthcoming collection––has the poet in

Mornington . . . going past the house where Captain Scott

last slept on civilised terra firma with his wife, Kathleen,

before setting off on his epic journey.

You can imagine him standing at the window in an alcove

looking dead south from the upstairs bedroom contemplating

the way ahead in his mind’s eye, the trail to the South Pole.

In Old Comrade, Hone Tuwhare’s drinking mate Jim Jamieson, before falling to his death, “shoulder[s] his way out / of the Crown [Hotel] and into the wind / at the corner of Rattray Street.”

He didn’t feel the hardness or coldness

of the pavement, for, like an old friend

come back, the wind held him as he fell.

A departure that anyone who has walked into the wind howling up Rattray Street in winter will comprehend.

In Walking down Elder Street “Dropping down the steps from Heriot Row into Elder Street, / Knox Church and Dunedin North spread out like a tray / of hot cross buns”, Peter Olds remembers

––Number 10 where I lived and wrote

for five years in the late ’70s and early ’80s,

. . . .

A rooming-house supreme.

A kind of sheltered workshop for poets and strays.

Dunedin. A city of psychiatric clinics, pubs and bookstores …

He shifts North he says:

to get off pills and psychiatric.

Caught the last NZR bus out of the city …

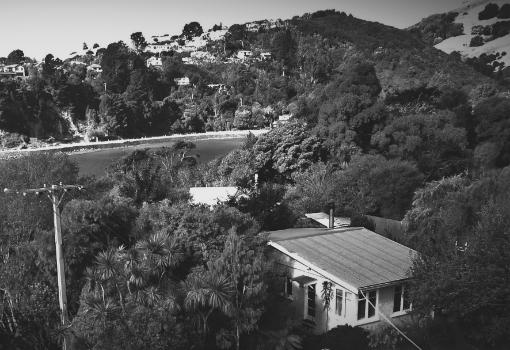

I soon missed the view of the peninsula

through the poplars from the French door.

I could stand there for hours in autumn

mesmerized by the fog rolling off the dark brown hills.

Olds locates news of another significant departure in a specific Dunedin location in The special: “I first heard about Jerusalem from Baxter himself. / We were standing on the corner of Cosy Dell / and Drivers Road and he was in an agitated state / like someone on an unnnatural high. // ‘God told me in a dream to go to Jerusalem’, he said.”

In the final poem of HOME GROUND, The Clear, which is the park above the town Ruth Dallas would take him to when he was dying, & where there is now a plaque bearing this very poem, Charles Brasch looks looks out, as he always did, beyond Dunedin:

It is all the sky

Looks down on this one spot,

All the mountains that gather

In these rough bleak small hills

To blow their great breath on me,

And the sea that glances in

With shining eye from his epic southern prairies

. . .

The Clear is a place of refuge too for Peter Olds. In ‘The Clear’: Prospect Park (to Charles Brasch), he writes:

Here, I can own you.

Here, on this seat they’ve placed in your honour,

there’s nobody to move me on.

There’s nobody to tell me my poems are good or bad.

There’s only Saturday evening cars going up and down

Lachlan Avenue,

to the supermarket, coffee shop, bottle store––

who cares?

All that matters is I can own you this short time––

have you to myself . . .

Childishly I ask for a sign:

a sign of some sort to show me the way clear,

a path that might lead to some meaningful place.

Not long before his death, when they were both patients in different wards of Wakari Hospital, Brasch had written to Olds,:

Fellow, fellow-stranger, how can I reach you

By word or sign? We scarcely know each other.

We exchange a smile and greeting in the street

By chance, or in a packed interval at the Globe,

But too much seeming seems to separate us,

Years, custom, the habit of reserve.

Yet I think of you as one who goes

Up the mountain in shadow, where I would go,

Not knowing who I am, or why I must,

With yellow robe and begging bowl.

Finally, in a late poem, Calm Evening, Dunedin, a less troubled Ruth Dallas leans into the ineffable:

9 p.m. and the sun still shining.

The city deserted.

The construction cranes

Make no more gestures in the blue sky.

The builders are far away

In their holiday houses.

The old year nods its head,

The new year not yet come.

Sparrows, who have no calendar,

Chatter in the linden trees.

My shadow grown tall as a telegraph pole

Slants across the quiet streets.

Tonight I should like to go on walking

Forever.

. . . A fitting end to this brief quest for truth on Dunedin streets, where, as in Dante’s Purgatorio, poetry rises up from the dead, & perhaps, whether it’s on a summer’s evening, in a grim southerly blast, or in a greasy fish & chip shop doorway, the soul of man is cleansed “and prepared to climb unto the stars”, since Dunedin, like anywhere else, is not only “a setting for something to take place in”, but “a place to go on from”.

But perhaps too, after all, a place for the poet “walking sorely” with “feet bruised” & “heart ill-used” to rest a moment, as the town croons into the ear of a weary R. A. K. Mason, in his uncollected Song for Dunedin:

‘For a year you may rest your head on my breast,

And a song at the most for payment:

Lie by me here for all a year

And I’ll cradle you full sweetly:

But if you will stay for a year and a day,

Then I’ll have your heart completely.’

Roger Hickin, 2016