Short story: The Mysteries of My Sister, by Barbara Else

By newsroom - Barbara Else | Posted: Tuesday Jun 20, 2023

A family saga in 10 instalments

The first

When she came to live with us I was too young to take notice of anything except the sandpit where I dug burrow after burrow for my toy soldiers and farm animals.

For the next two or three years, after school I kicked a ball around on the bus turn and gave cheek to the drivers. My best friend was Rob Green. Mum and Dad said that he was a rough sort, which made him sound pretty exciting. I figure now, it meant his parents weren’t Anglican and didn’t use jam spoons or butter knives. Nor did I, but at least Mum always had them on the table.

The only time I said something to Mum about Julie was when she must have been thirteen or fourteen. I’d have been eight? Nine?

"Where is Julie a cousin from?" Not well-worded, but the thought had only just appeared in my head.

Mum dumped a lump of dough out of a bowl and started knuckling it. "Have you practised piano? If not, do it now."

I supposed I’d been ignorant or careless not to know it was normal, that when a cousin five years older than you lived with your family long enough she ended up being called your sister. A tidy way of doing things, I reckoned.

Mum knew I hated piano. We had rows about it all the time. How was fumbling through Here we go/Up the row/To a birthday party ever going to be ‘good for me’?

Julie had left a couple of hair clips next to the keyboard. I used one to scratch Middle C so I’d find it with no mucking about.

The second

Two years later my parents were still paying for piano lessons. The teacher and I used to laugh at each other’s jokes and most often she let me out early. I was still nicking off to play with Rob. We’d graduated, so to speak, from annoying the bus drivers to excavating a hide-out in some cleared ground at the end of the turn around. A sweaty, muddy job, a secret job.

Julie was old enough to have boyfriends now or at least go to Bible Class dances. My real sister, Sally, two years younger than me, a blonde butter-ball of energy as one of Mum’s friends called her, was fascinated by the getting-ready. Julie’d had a bad couple of weeks, crying and shutting herself away. I’d no idea why. Boyfriend trouble? Periods (which I had no idea about then and little more now)? But the new dance dress, Mum sticking pins in at the waist, measuring the hem, doing other women’s stuff with her, had seen her come right again.

Now Julie sat at her dressing table, Sally leaning over her shoulder, the pair of them sharing girl secrets. It was like watching something alien, when you’re keen to get closer but need to find more out before you dare.

The hair rollers had been first, Julie setting them in with long white pins, sitting under the plastic bonnet while the hot air blew, then Sally helping her take the pins out. Next was some backcombing and hairspray. Then the dab of powder on Julie’s nose, and her first lipstick, not allowed any till that age, my parents were unshakeable. It looked orange but went pale pink on her lips.

Julie waved the lipstick at me: ‘Want some?’ I half put out my hand, they burst into laughter and I ran. I’d only wanted to see how it could turn from orange to pink.

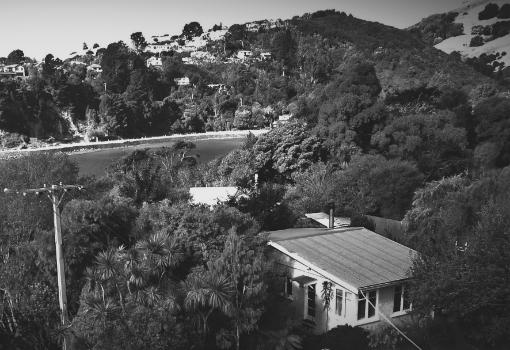

Late that night I caught sight of her outside the back door. I must have been reading later than I was allowed, and heard her. A boyfriend had his arms round her shoulders, they were close, front to front. His name was Gregory. He dressed in black, had olive skin and smooth dark hair. I hesitated, as you do. He was saying, ‘When we’re married we’ll have a black ceiling in the kitchen.’ I realised there were unknown numbers of decisions you’d have to make in your life.

The third

She broke up with Gregory.

The fourth

Finally I was allowed to ditch the piano. I’d promised to take something else creative in its place. Mum and Dad were keen on a rounded education: that generation had some wisdom. I chose art lessons.

By now, anything that wasn’t to do with sport, I kept quiet from the boys in the street. The hide-out was gone: after a storm we found it had collapsed, a pit of mud, all our stuff buried, and runnels of terror went through me. A few weeks later a house was being built on the site.

Our fathers warned each one of us, if we went near the construction at any time, they’d have our guts for garters. I watched though, and studied the bracing. Now and then one of the builders took a moment to explain to me about joists, dwangs, and weight-bearing beams. The art teacher reckoned my sense of perspective was rocketing.

All of a sudden, it seemed to me, Julie was engaged to a man called Terry, five years older than her. His parents had a country store forty minutes outside Whangarei. He was youngest of seven. The only other brother, the oldest, had long left home. The girls were all married by this time, as well. His mother sounded strange. When the kids were growing up, she had them serve their own dinner in order of age, and made them sit on towels in case they mucked up the chairs. There were only ever scrapings left for Terry, and he’d always cry.

"So by the time it was Terry’s turn, he was Terry damp-towel." Though I was sorry for the little kid I still thought it was a hilarious joke. Well, hell, I was thirteen. Mum was not impressed.

I was invited to go up and stay at the house behind the store. No way. I wasn’t sure his mother would have guest towels. I suppose I could have taken my own but I’m glad I didn’t think of that at the time.

The fifth

I heard a murmur among Mum’s friends that Julie’s wedding was ‘a bit rushed’ though I didn’t understand any of that for years. She was only eighteen of course. But there wasn’t a baby. Never.

I didn’t like Terry. Everything Julie tried, like pottery, he’d try too, then tell her how wrong she was doing it. Worst thing, he hung his own craftwork in their house on the Whangarei outskirts, macrame pot plant holders, hand spun wool like off a sheep you’d see drowned in a ditch.

"Your stuff’s far better," I said to her once.

Julie said, "Hush. Let him feel best."More loudly, she said laughing to Terry: "He’s only being a nice little brother."

I hated her when she told him I’d become good at art, which I wasn’t, just interested in it. Your mind went quiet when you were working something out on a sketch pad — there’s nothing between you and the paper.

But Terry began pestering me to show him. I stopped visiting them for other reasons too that I couldn’t express to myself. I managed not to be around if they drove down to Auckland to see Mum and Dad.

Julie left him in the end, with bruises on her arms, which facts, fading over a long time from purple to yellow, the rest of the family didn’t talk about.

But I’d seen Terry knock her against the back of their car once when the boot was up, and she hit her head on the edge. Julie and Terry both pretended it hadn’t happened but her scalp was bleeding. I’d wanted to grab the rake that was lying nearby and strike him so he fell face down in the gravel then I’d tramp that big grinning head into it. I imagined doing exactly that for a few years.

The sixth

She went back to Terry. I was in my twenties, starting a Master in Engineering in Wellington. Feeling sorry for him, was my guess, he could put on one hell of a pitiful look. I finally told Dad about the shove I’d seen.

"Between married people," he said. "Keep your nose out. And remember this isn’t a family that gossips."

The seventh

I kept my nose well out, never visited her and Terry. My parents said I should. "I’ve too much work on, I’m keeping my nose out," I said, and Dad got the reference.

Julie herself said our parents could leave me alone.

Later, one time she came down to Wellington by herself for some rural government thing, and whispered it was much the best if I didn’t visit. She also muttered, was I ever going to get a girl friend?

Much the best if I didn’t, I thought and felt grateful that she seemed to understand me.

The eighth

In 1985 Terry died after falling into a pot hole outside their gate. The Council knew about it but hadn’t done anything. My theory is, city and town councils have a secret annual contest for the longest list of unfilled potholes. Terry had probably tripped on the cattle stop. It wasn’t the pot hole so much as it being full of cattle muck that got into his lungs. Who says we don’t need so many cows?

At the funeral Julie said and did all the things you’d expect from a widow. Her face was smooth, rosy like a teenager’s. "It hasn’t sunk in yet," my mother said. I thought my sister looked better than she had since her wedding.

Engineering as a profession needed social reconstruction though the term wasn’t much in use at that time. Not where I worked with a big building contractor. That place had a hard time accepting that the Homosexual Law Reform Bill had even been been thought of. No way was that going to pass, loud laughs clanging round the lunchroom. It was then I managed a series of paintings that half pleased me, rungs like ladders or cages with colours the sort Julie had started to wear again, not navy and brown like Terry told her to, but brighter, blue ranging to purple, coming out of the shadows.

The ninth

Mum and Dad held their Sixtieth Wedding in the local church hall in Mt Eden, fifty people allowed. Covid was at bay, for a while at least, and social distancing not so necessary.

Julie and Sally had their heads together at one of the tables. They both worked in libraries, believe it or not, Julie in admin, Sally an actual librarian. Clever people. My sisters, Julie with purple flashes in silver hair, Sally with a flaming red pixie cut.

What was so funny? I drew a chair up. "Your hair suits you," I told them both.

"So does yours," said Sally. That got a fresh laugh. I shaved it all daily.

"Times have changed," Julie said. She meant, silver hair being fashionable now, and being bald was trendy, even desirable.

"How are you," they asked. I gave the shrug that says same as.

"You were laughing," I said. "Girl talk?"

They shared a look, and a nod, let him into it.

Sally went on, "You’d have flicked out that Terry was gay. When?"

I had, yes, when I followed media interest before and after the Law Reform, which had passed by one vote. It explained his deep anger and even stupidity. If you can’t understand who you are yourself, how can you have any insight about anyone or anything else?

"He’d have thought he had to get married," I said. "A small town Northland boy in 1974? Poor guy probably thought marriage would ‘cure’ him. Or disguise him at least. It’s no excuse, though."

Julie let out a sound, part laugh and part anger about her own wrecked life. She’d never married again.

"I wondered if you’d pushed him into the pothole," I said. "Joke, not a joke. Wishful thinking in its way. I wished I’d pushed him."

She laughed again, part sadness. "I grew sorry for him, as much as anything."

As I’d thought, then.

"Conforming," Sally said. "It’s a bastard. You’re all right, though?" she asked me. "Our loner?"

I was all right. I hadn’t found anyone to settle with, too used to being on my own. But my painting was doing okay, a real surprise, plus I had my own good consulting business in construction design.

"I’m very all right."Julie fluffed the purple streaks in her hair. The pair of them laughed again, the particular way they’d been doing when I pulled up my chair.

"Tell him," said Sally. "He’s your little brother."

"Well, then," said Julie laughing. "I got a boyfriend."

The first real one — she meant straight one — since long-ago Gregory. She’d been having some very good times in the sack, the pit, the bedroom. At last. At age sixty five, that was brilliant, and high time, wasn’t it?

"So,’ I said, "when am I going to meet him?"

"Never." Julie reared back, grinning. "I’ve got rid of him. That’s all he wanted me for, very old-fashioned ideas there, I soon found out. It’s taken me long enough to realise I don’t have to do the expected any more, do I."

The tenth

Sally heaved herself up and set off for the table where her grown up kids were laughing with their own nearly-grown kids. "Nice to see one of us doing things the conventional way," I said. "Mum and Dad’ll like that."

"Not that they were exactly conventional," Julie said.

"They were," I said. "They are."

Quizzical, is how she looked. "Yes. But think about me."

"You? Well, yeah, they adopted you, or whatever. I’ve never thought of you as anything but my sister —"

I had asked Mum that once, and got no answer. I hadn’t asked a second time. What a selfish brat, and I was still selfish. "Sorry. I never thought about what happened to your parents — my uncle and aunt? Do I even know their names?"

She swatted my arm, more like a pat. "I spent my first eight years in an orphanage. But I am your sister."

She stood up more easily than Sally, and headed for the dessert table.

I turned my head as if there’d be a diagram pinned up on the walls to explain it. What I saw was Mum and Dad, both eighty-one, Mum with a blush, Dad with that goofy soft look still behaving like a man in love, the bouquet of sixty red roses on the top table, one for each year.

My brain took a while to do the processing. They must have been in love for over sixty-five years. Mum’d had Julie when she and Dad were teenagers — they’d been made to wait till they’d turned 21 before they could marry? Then who decided they should wait another few years before taking Julie out of the orphanage? Is that why they’d let her get married at only 18, when she knew bloody nothing about men?

It was still filtering in, the diagram shaping up line by line. Julie was only able to come and live with us when everyone could pretend that she was a cousin. Then slowly, slowly, Mum and Dad could start saying the truth disguised as kindness.

All of us, then, forced to conform or letting conformity shape us. Sally was the only one who wasn’t constricted and lived her conventional life with true grace, like a high-sailed yacht through all social occasions.

I’d always wanted to ask Julie why she broke up with Gregory. Either, I guessed, because our parents, maybe our grandparents, said something like he was part-Maori, or all-Catholic, so it wouldn’t work. She might not even remember him, or what he’d said.

In the first townhouses I’d developed from rough plans through to the outside planting, I tried a black kitchen ceiling. The tenants might have been surprised but they grew used to it. I made sure it was the right lighting. It was never oppressive.

The new memoir Laughing at the Dark by Barbara Else (Penguin Random House, $40) is available in bookstores nationwide.