A Tale of Two Cities (Of Literature)

By Philip Temple | Posted: Monday Jan 09, 2017

‘Chance is a fine thing’, the title of my 2009 memoir would have it, and chance had it that the start of our 2016 travel plans fitted precisely with the Literatur Herbst(autumn literature) festival in Heidelberg.

Heidelberg had become a UNESCO City of Literature at

the same time as Dunedin in 2014 and the opportunity to establish a tangible

link was too good to pass up. Although we almost passed out from jet lag

when, on the evening of our arrival from New Zealand, we were front row guests

at the opening event of the festival which was an extended performance of

medieval German DADA poetry!

Our own session the following evening, 16 September, was less stressful. We had an appreciative audience for ‘Literarische Stimmen aus Dunedin’ (‘Literary voices from Dunedin’) when Diane read from her poetic narrative Taking My Mother to the Opera and I read from my last novel MiStory. The planned 75-minute session ran to two hours as people engaged with the themes of the books under the expert guidance of moderator Jutta Wagner, as well as discussions about Dunedin and New Zealand writing.

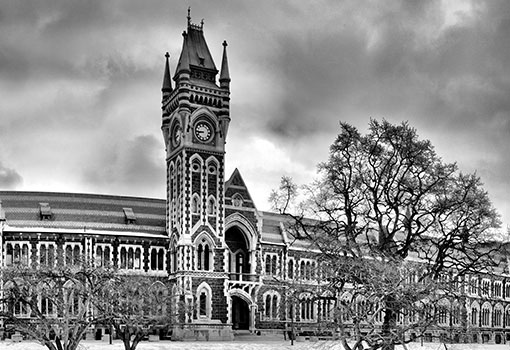

Heidelberg and Dunedin are of a roughly similar size and, apart from the UNESCO connection, they also have in common that they are home to their country’s oldest universities. But the fact that the University of Otago is 150 years old and the University of Heidelberg more than 600 underlines difference rather than commonality. Heidelberg Man, a precursor to Homo sapiens from 300,000 years ago was found nearby in 1907, and the city’s main shopping street, Hauptstrasse, advertises its Roman origins by running long and straight for three kilometres. The red-roofed city with its castle and many ancient buildings straddles the Neckar River where it runs out through the hills of the Forest of Oden and on to the upper Rhineland plains. It embodies the usual central European history of fortification and war and destruction and more fortification and war and destruction.

The ‘myth’ of Heidelberg, perhaps better described as its legendary literary history, stretches back to the Middle Ages (and its DADA poets) and is expressed both as a motif in German poetry and a place where writers live. The list of literary luminaries who have frequented Heidelberg is impressive, even overwhelming, but their sojourns and writings continue to provide an endless source of scholarship for students, biographers, bibliographers and translators. There is also a thriving community of contemporary writers across all genres, including a number who have settled there from other countries, all of whom find the density and complexity of the city’s literary fabric a source of intellectual security and inspiration. Although it is said that anyone who settles in Heidelberg sometimes feel like a museum attendant there is always new creative work bubbling under the surface of the city’s ancient facades.

Probably the most famous era of Heidelberg literary history was the ‘glorious romanticism’ of the early 19th century and which swept Europe at large. Friedrich Hölderlin, Clemens Brentano, his sister Bettina von Arnim and brother-in-law Achim von Arnim were the leading figures in a movement which celebrated old German folk literature and led to a three-volume work Des Knaben Wunderhorn - Alte Deutsche Lieder (‘The Boy’s Magic Horn - Old German Songs) that were to inspire the music of Schumann, Brahms and Mahler.

But Heidelberg is almost as notable for its philosophers as its writers. When we walked along the Philosophenweg, a popular walking track through old vineyards above the south bank of the Neckar, we were conscious that we trod not only in the steps of Brentano and Von Arnim, but also Hegel and especially those 20th century philosophers (and psychiatrists) Max Weber, Karl Jaspers, his student Hannah Arendt, Erich Fromm and Walter Benjamin.

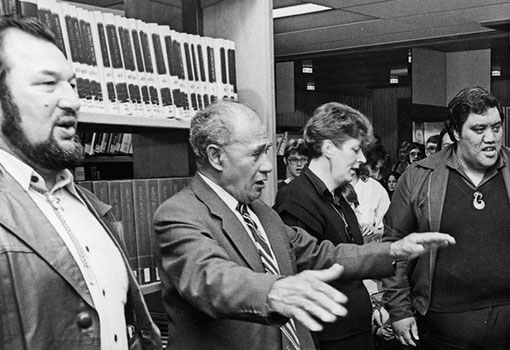

Not only Philosophenweg but virtually every street and alley in old Heidelberg is laden with the freight of literature and philosophy. There are about 20 bookshops, including the antiquarian, and a similar number of publishers, many of whom specialise in scientific works generated by the university and a thriving translation industry. There is more than one literature festival and events each year across a variety of venues. These are not all rooted in the city’s literary history and tradition: contemporary writers from all over Europe and Germany are drawn in. Heidelberg is even noted for being a cradle of hip hop and rap. This came about from the city being the location for US Army headquarters from 1945 to 2014 and local kids caught the New York wave from the early 1980s through the strong American cultural influence. Although the troops are gone, the DAI remains - the Deutsch-Amerikanisches Institut - with its fabulous library where Diane and I had our festival session.

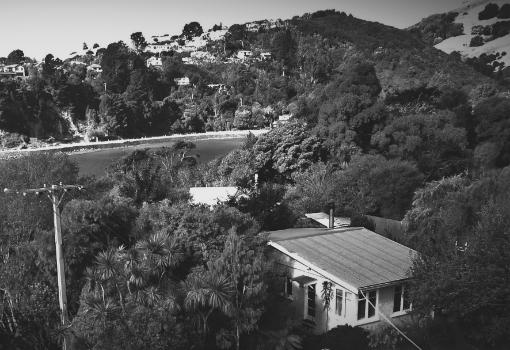

At first sight, it seems that the scale and variety of literary history and activity in Heidelberg loom large over Dunedin by comparison. But Heidelberg’s literary eminence is the consequence of centuries of creative endeavour founded on thousands of years of life and work and tradition within one wider cultural and linguistic environment. Dunedin’s literary history is considerably less than 200 years old and grew first as an outpost of larger and older British cultural and linguistic traditions. Now we have our own strong and growing tradition, as the Octagon plaques attest, and if Heidelberg have Brentano, Von Arnim and Hölderlin, we have Brasch, Baxter and Frame.

We can, nevertheless, look at what Heidelberg has, what it has developed, and what we may still do here. To begin with, I will point only to Heidelberg’s literary prizes; in particular the Clemens Brentano Prize which is awarded annually - worth 10,000 Euros - to works of poetry, fiction and non-fiction in rotation. This is something we can do. How about the Charles Brasch Prize from Dunedin UNESCO City of Literature, awarded in the same way? Let’s think about it - and then do it.