Book of the Week: Crime is endless, time is short

By newsroom - Guy Somerset | Posted: Friday Mar 18, 2022

Britain's best crime novelist who lives in Dunedin

Towards the end of Liam McIlvanney’s fourth novel, The Heretic, one of his Scottish detectives notes that a basic rule of police work is: “Don’t tie a Windsor when a simple knot will do.”

Crime is endless and time is short, goes the Glasgow police force credo. No need to complicate your thinking when there’s an obvious explanation staring you in the face. What’s true – or considered true – for crime fighting isn’t necessarily true for crime writing and McIlvanney is very much a Windsor knot kind of crime writer. Both his detectives and readers have to up their game in his novels. The obvious explanation is seldom the right one and the complicated thinking needed to unravel what’s going on is testament not only to his detectives but moreover to McIlvanney, the writer who ravelled the plots in the first place.

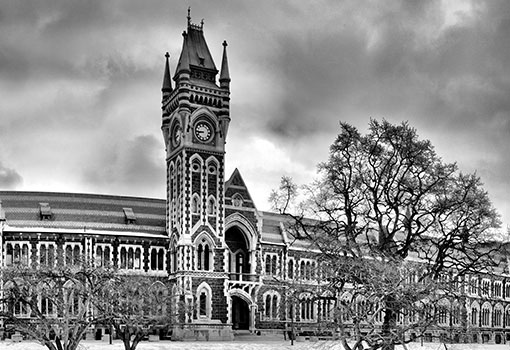

The Heretic is McIlvanney’s sequel to his 2018 novel, The Quaker, winner of that year’s Bloody Scotland McIlvanney Prize for Scottish crime book of the year. The prize is named for McIlvanney’s father, William McIlvanney (1936–2015), a Scottish crime-writing legend often described as “the Godfather of Tartan Noir”. It should be added that The Heretic and The Quaker – alongside McIlvanney’s first brace of novels, All the Colours of the Town (2009) and its sequel, Where the Dead Men Go (2013) – are steeped in Scottish life (and death) but were written in Dunedin, where their author is Sturt Professor of Scottish Studies at the University of Otago.

They say absence makes the heart grow fonder; it’s made McIlvanney more gimlet-eyed about Scotland and in particular Glasgow, whether in the present of his first two novels or the 1960s and 70s of his latest.

Writing from so far away has perhaps also made McIlvanney’s imagination more daring in where it’s prepared to venture and the leaps it takes when it gets there. This was especially evident in The Quaker, in which McIlvanney borrowed boldly from one of Glasgow’s most notorious (and unsolved) criminal cases, the 1968 and 1969 ‘Bible John’ rape and murder of three women, and reimagined it with a balance of fealty to the facts and free invention worthy of such classics of the genre as James Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia (1987), David Peace’s Red Riding Quartet (1999–2002) and Emlyn Williams’s non-fiction novel Beyond Belief: A Chronicle of Murder and Its Detection (1967) about the child killings of Ian Brady and Myra Hindley.

McIlvanney’s fealty to the facts may have left some readers askance at the repellently misogynistic details of the renamed ‘Quaker’ murders, but they should be assured these were the doing of Bible John and not a dubious feat of imagination on McIlvanney’s part.

Left to his own devices in The Heretic, without a known case as a model, McIlvanney’s violence is far less baroque and more grounded in the day-to-day criminal activities of his characters, place and period.

The Heretic picks up The Quaker’s story in the summer of 1975. The previous novel’s lead cop, Detective Inspector Duncan McCormack, is investigating the successor to the gang leader at the centre of The Quaker; an arson attack on a warehouse from which the fire spread to a neighbouring tenement block killing four residents; and a pub bombing.

The Windsor of McIlvanney’s plot is knotted tight, both in The Heretic itself and in its connections to its predecessor. Readers need their wits about them to keep on top of it all, let alone steal a march on McCormack and his team of detectives.

As in The Quaker – and to a lesser but still alarming extent in the more contemporary All the Colours of the Town and Where the Dead Men Go – the Glasgow and wider Scotland McIlvanney depicts is rife with criminal gangs and police and political corruption and riven by religious (Protestants vs Catholics) and geographical (the city vs the Highlands) sectarianism. Sexual sectarianism too, be it the subterfuges needed by gay McCormack in a country where sex between men remained illegal until 1980 (13 years after being decriminalised in England and Wales) or the treatment by fellow police of Detective Constable Liz Nicol in a force that until recently exiled female officers to a Women’s Department to serve as lackeys to their male colleagues.

McIlvanney’s storytelling – his scattering and then solving of clues, the characters he draws, the jeopardy he puts them in, the tension he ratchets throughout – will have you racing through The Heretic, but you should force yourself to slow down to savour the quality of his writing. He has an acute eye for period and place and the accumulation of small details that make a scene true to life. Some of these details turn out to be clues too. And sometimes opening a packet of crisps is just opening a packet of crisps.

McIlvanney is a close observer of human behaviour and there’s a convincing psychological continuity to characters. So, after a detective finds a building in a narrow lane leaves no vantage point from which to view and appreciate it as one of the city’s architectural treasures, it makes complete sense he should think of it a few minutes later when an interviewee leans in so close he can’t see her properly.

McIlvanney’s not afraid to probe psychological perversity either, with McCormack standing at a window and pondering how: “Everything in his vision looked sharp and fresh: the little bubbles and imperfections on the brickwork of the window; the flaking green paint of the frame; the patterns and perforations on the greying lace curtain he was holding aside. He’d noticed this before, how a murder renewed things. Like the city after a shower of rain. Everything renewed and expectant.”

It's a general rule of thumb that when a reviewer praises the prose in a novel and presents a sentence or two as examples they will be lines of mind-numbing mundanity.

But I’ll happily stake my credibility on McIlvanney’s description of the “polis knock” as “three measured blows, the kind of summons that Death might attempt with the butt of his scythe”.

A character lights a match, “watching the yellow sail of flame climb the blackened stick”.

And keeping with flames, the tenement blaze that ignites the novel: “Swooping and diving and wheeling round the landing are ravens, bats, demons – no, shadows – thrown madly about by the flames that clamour and climb to catch and pluck at them from the stairwell.”

A pathologist raising his arms “to shoot the loose cuffs of his surgical gown” looks “like a moorland prophet”.

Tell me that isn’t good.

As in The Quaker, McIlvanney takes us into the heads of his victims and criminals as well as the detectives investigating them and evinces empathy where we don’t expect it.

His Glaswegian vernacular is piquant and, although his detectives are more evolved than their colleagues elsewhere in the force, Nicol isn’t above the line: “The nonce wing, where they shoot their load in your macaroni cheese.”

Another line, McCormack referencing Anton Chekhov when talking to the principal villain about a gun, seems less likely and too knowing of McIlvanney. It sticks out like the rarefied reading matter – “Ambler, Greene, a Josephine Tey” – found on top of a crim’s porn mag in The Quaker. When McCormack muses on “Sillitoe’s Cossacks”, I thought, oh no, McIlvanney’s really getting carried away now. But no, this Sillitoe isn’t Alan, author of The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, but, rather, Percy, Glasgow’s real-life 1930s chief constable.

A bigger slip for McIlvanney is the virtually flawless spelling and punctuation in a series of letters supposedly written by a poorly educated sex worker (or ‘hoor’, in the local argot). She doesn’t use semi-colons but I spied at least one colon. McIlvanney would be lucky to get such a well-written letter from one of his university colleagues.

Tightly knotted though the plot is, the novel as a whole could be tauter, a trimmer 400 pages (like The Quaker) instead of the 500 it is. It drifts at times and the reader’s attention drifts with it.

But The Heretic is another substantial achievement for McIlvanney. The reader finishes it closely acquainted with the Glasgow it depicts and the characters who live there, and eager to renew that acquaintanceship as soon as possible. Here’s hoping McIlvanney doesn’t limit McCormack to two novels as he has so far journalist Gerry Conway from All the Colours of the Town and Where the Dead Men Go.

You want to stay in the world McIlvanney has created, just as one of his characters wanted as a child to stay in the world of the backcourts of Glasgow’s tenements: “The railings between the courts had been taken away. In the war, like. And some of the walls had been knocked through. It meant you could go from one end of our street to the other without leaving the backcourts. It was like a secret street […] The bit I remember is, there were people who would ignore you if you passed them on the street, but in the backcourts? They’d say hello, maybe slip you a tanner. It got so I never wanted to go anywhere you couldn’t get to by the secret street.”

The Heretic by Liam McIlvanney (HarperCollins, $32.99)

View Original Article HERE