Strong Words 3 Extract:

By Kete Books | Posted: Monday Sep 18, 2023

Reasons to Learn Cantonese by Maddie Ballard from Strong Words 3: The Best of the Landfall Essay Competition

Reasons to Learn Cantonese by Maddie Ballard — Kete Books

1

My grandfather gave me my name at birth:文麗 | Mun4 Lai6. The first character, a family name, means the arts; the second means beautiful. Years later, when we lived in the same city, he made me practise the characters in long columns to get the strokes just right, this stern old man whose every smile had to be earned.公公 | Gung1 Gung1 was himself a master calligrapher: he had the traditional ink and brushes, which I was not allowed to touch, and had painted placards all around the house.

When I was asked as a child what my middle name was, I gave the German middle name my parents had chosen, Elisabeth, which already seemed unusual enough for its spelling. I pretended often to have no other middle name. Now, I consider the love promised in naming a child and the hurt of rejecting such a gift.

2

When I studied German, I copied out page after page of irregular verbs until I knew the whole song: befehlen, befahl, befohlen; gelingt, gelang, gelungen. It took me a whole year to learn all of them, from backen to zwingen, but it’s a finite list; the same every time I google ‘irregular German verbs’. Mastering it,

I immediately began to sound less like a foreigner.

Tense construction in Cantonese is simpler, relying on context or a single modifier. You do not have to say I went to the airport, you can say I go to the airport yesterday. There are no irregular verbs. There is also no separate plural form for most nouns, and only one pronoun for he and she. On the other hand, I can’t guess a single new word, because nothing looks like English. On the other hand, there is no alphabet, only many thousands of distinct characters. On the other hand, the language uses a complex system of units whenever a noun is presented with a quantity. One apple, 一个苹果 | yat1 go3 ping4 gwo2, means something like one of the apple—only the unit, of the, changes depending on the noun. Apple and orange use the unit for small, round things. Cucumber and whole fish use the unit for long, thin things. This seems intuitive until I learn that hour and person and television also use the unit for small, round things. There is no finite list of verbs I can memorise, and I am still trying to figure out how I can make myself sound less like a foreigner.

3

There are so many words I already know. At least one appears in each class, waving at me from a mass of unintelligible others, like a small friend. 快啲 | Faai3 di1 laa1 (hurry up), 垃圾 | laap6 saap3 (rubbish), 洗手 | sai2 sau2 (wash your hands), 瞓覺 | faan3 gau3 (sleeping). For almost two years of my childhood, we lived in my grandparents’ house, where rice was eaten with every dinner and the placards on the wall promised 长寿 (longevity) and 和平 (peace). Under the erosions of my white schooling, I did not think I had kept so much.

4

Cantonese contains at least six tones: the same word, said with minutely different inflections, can mean four or dead. Something about this reminds me of wordless nature: the language of birds wheeling over the lake, or the dim that comes over the earth during an eclipse. I did not think there was a language closer to those things than English, in which I can write anything I like. But it turns out writing is the opposite of a certain kind of knowledge.

5

While we don’t learn to write or read the characters, they are printed on our handouts. I’m amazed at how close some of the words look to what they mean; at what seems, to an English speaker, like the collapse of signifier and signified:狗 (dog); 人 (person); 木 (tree); 雨 (rain). The word rain in English is so familiar to me it’s almost invisible, but beneath the surface teem a host of unconscious associations: echoes of the words ray and pain and reign and rein; a certain openness implied by the vowel. In Cantonese, the homonyms of 雨 | jyu5 include宇 | jyu5 (space), 語 | jyu5 (language), and 羽 | jyu5 (feather). I am only beginning to imagine a world in which rain is unconsciously associated with feathers.

6

When the war come, the first son, he swim to Hong Kong, the second son, he … She does not have the English to finish. But I would like to know what happened to the second son, and the third, and their mother.

7

Every few weeks, I video call my friend Willa, who speaks Cantonese fluently. With her, I practise the names of fruits I have learnt—苹果 | ping4 gwo2 (apple),橙 | chaang2 (orange), 西瓜 | saai1 gwaa1 (watermelon). What about pomelos? she asks. I tell her we didn’t learn the word for pomelo and she looks appalled.

But it’s an important fruit! she says, which makes me so fond of her I feel like crying. I met Willa when she was doing a Law master’s degree in English, her fourth language. Once, she asked me to check an essay for her, where not one word was out of place. Now she teaches me the word 柚 | jau2 (pomelo) with such patience, I’m reminded language exists only to bridge two people.

8

One year, in London, my flatmate’s extended family came around for Christmas lunch. I came downstairs to say hello. Oh, said her mother to me, are you the children’s nanny? No no, this is my flatmate, said my flatmate. Oh, but I thought, said her mother, but she did not finish her thought, which hung understood in the air. Nobody apologised. I left the room. It might not have been racial, said my white boyfriend later.

9

My father is a white man. Once, when we are out for lunch together, the waiter hesitates for a second, then says to him and what will your wife have? and I remember again, as I do every time we are together, that I do not look like him. I will always be unlike my father, which is a kind of grief. Part of me wishes I could be only white. Another part is furious I could ever have such a wish.

10

There are so many questions I cannot ask in English: What was the trip like? Were you frightened? How did people treat you when you arrived? What is the worst thing a New Zealander has ever said to you? Do you ever regret coming here? What lives did you hope for, for your children? Do you think they got them? Will you give my children Chinese names, even if they do not look Chinese? Are you lonely?

11

Why are you learning Cantonese? I am asked almost every time I mention it. What made you start now? Where exactly, says someone leaning in to parse my face, are you from? I am a walking question, one that strangers stop to ask. But I still don’t know the answer. What does it mean to be half-Chinese? How do you carry the genes of both a group that is regularly discriminated against and a group that regularly discriminates in one body? Who are you in the eyes of the world and who are you quietly, within yourself? I am the custodian of a body that could never pass for white. More than anything, I would like to know myself.

12

I wanted to write about learning German. I learned German because I loved the serpentine grammar, because I romanticise Bach, and because I wanted, once, to be other than myself. I worked at it until I mastered it, and all my work was joy.

Learning Cantonese is about guilt and obligation and wist. I am slow and I do not love it, partly because it does not feel quite like my choice. In its thickets, I cannot pretend to be other than myself. I do not think I will ever master it.

13

I don’t study as much as I should between classes, although I think about the fact I cannot speak it every single day.

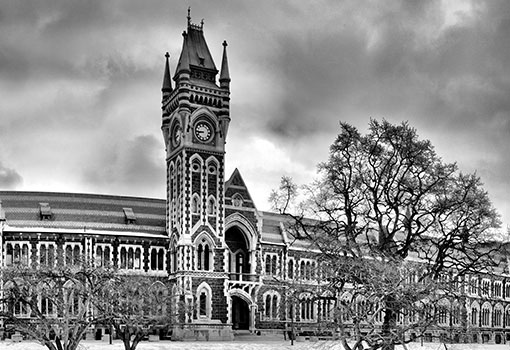

‘Reasons to Learn Cantonese’ by Maddie Ballard was first published in Strong Words 3: The Best of the Landfall Essay Competition selected by Emma Neale and Lynley Edmeades (Otago University Press, $35). Strong Words is a series of essay collections that celebrates the best essays entered into New Zealand’s prestigious, annual essay competition, the Landfall Essay Competition. Find out more about this competition at oup.nz/landfall-essay-competitionMaddie Ballard is a Chinese-Pākehā writer from Tāmaki Makaurau. She is undertaking a master’s in creative writing at the International Institute of Modern Letters. Her writing has appeared in Starling, The Pantograph Punch and Turbine|Kapohau.