Why Go Girl needed to be written

By The Sapling | Posted: Tuesday Apr 03, 2018

New Zealand's answer to Goodnight Stories for Rebel Girls is in bookshops now. It's called Go Girl: A Storybook of Epic NZ Women (Penguin Random House NZ), and it's written by the multi-award-winning Barbara Else. We asked Barbara to tell us why the book was so badly needed, and we learned why she was the right woman for the job.

At primary school my favourite time was silent reading. I’d almost teleport to the class library shelf and grab a history book. They bristled with tales about male explorers, inventors and warriors – Charlemagne, Sir Frances Drake, Horatio holding the bridge, and so on. There was an occasional story about Madame Curie, Florence Nightingale, maybe Elizabeth Fry. I didn’t see a word about Aphra Behn, the 17th Century female writer, explorer and spy, till I was in my forties. At school I certainly didn’t see any other material about talented, even ground-breaking female artists and inventors.

Fairly early, though, I was a feminist – or at least a puzzled girl who wondered why there wasn’t more sharing. For instance, a trivial example: why did the only boy in my family deserve two lamb chops if there was a spare? Why couldn’t the three sisters take turns with him for any extra?

[W]hy did the only boy in my family deserve two lamb chops if there was a spare? Why couldn’t the three sisters take turns with him for any extra?

My parents supported my interests in reading and drama from my earliest days. But a not-so-subtle sexism operated in the family. I was too young to know at the time, but my older sister wanted to work for the police. She was well-organised and practical. She’d have been brilliant. But my parents and brother scoffed at her. It still hurts her all these years later – a barrier was there and she had no encouragement to climb over it.

I know that everyone is a creature of their conditioning. But some of us have always questioned that and found ways to overcome it as best we can. So yes, the world needs Rebel Girls with its true tales of remarkable women. There are several books like it now, including the magnificently titled picture book She Persisted (Chelsea Clinton and Alexandra Boiger, Penguin Random House). Girls and women need all these books. Maybe more so than girls, boys and men need them as well, to help break down those invisible barriers that still exist.

Maybe more so than girls, boys and men need [these books] as well, to help break down those invisible barriers that still exist.

Current research indicates that up to age seven girls generally aim to be anything at all when they grow up. After age seven, they begin to self-limit. That’s when the insidious tentacles of social conditioning begin to wrap around them. Only this February, a column in the Otago Daily Times described a four-year-old crushed with despair because ‘girls can’t be pilots.’ Who told her that? Not her mother. As the columnist said, Googling ‘Jean Batten book for pre-schoolers’ wasn’t going to cut it this time.

Arguments on social media against books like Rebel Girls include: ‘my son needs to be encouraged too.’ Of course he does. Nobody’s arguing. However boys have had their own books for decades – centuries. Addressing the imbalance is overdue by the same number of decades.

Soon, I hope, there’ll be books for children where stories about success alternate from one about a man to one about a woman, in equal balance right to the end with all manner of diversity laced through as it should be. And the ‘boy’ stories won’t just be about sport and exploring. They’ll include male choreographers, artists, musicians, social entrepreneurs, eco-warriors. The first book for boys along the Rebel Girls lines is Boys Who Dare to be Different (Hachette), due in New Zealand in mid-April. When I saw that advertised, I let out a cheer.

And of course New Zealand needs its own version of Rebel Girls. Even before I’d said ‘yes!’ to working on Go Girl, I thought, It must have diversity. I think we did the best we could. Any regrets I have are about the absence of some professions. I would love to show girls the beauties and excitement of the hard sciences. There wasn’t a woman engineer or architect we were able to use. (Early on, I discovered how many gatekeepers restrict access to most of these famous women – it’s not just their busy schedules, it’s agents and trusts and other protections.)

The point of the stories in Go Girl is to show how someone becomes successful.

The point of the stories in Go Girl is to show how someone becomes successful. Many of the stories are about failure and heartbreak as well as success. I found it hard to write some of the sadder stories. Could I include Beatrice Tinsley’s heartache for a readership that included seven-year-olds? (Yes.) How to write about Janet Frame’s formative experiences of family tragedy? The story of Ahu-mai te Paerata – the violence – but then her sense of fairness – oh my goodness, such a shattering story.

It was an unexpected blessing that the sequence ended with Yvette Williams, first New Zealand woman to win an Olympic gold medal. I focussed on her return to NZ several weeks after the Helsinki Games. She thought all the excitement would have died down by then. But the whole country celebrated. Isn’t that what any of us secretly long for? That when we return after our endeavours, people we love will open their arms and say well done.

The best result of Go Girl for me will be if girls, in public or private, feel confident about what they want to do with their lives and say, ‘I’ll try. I can find my own way.’

Barbara Else

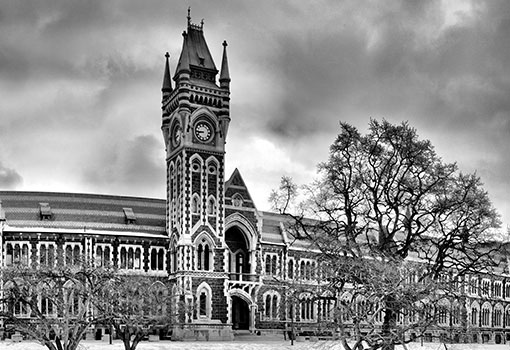

Barbara Else writes for adults and children, and has held the University of Victoria Writing Fellowship and the University of Otago College of Education/Creative New Zealand Children’s Writing Fellowship. She has also been awarded the Margaret Mahy Medal. Her most recent novels for children are the Tales of Fontania Quartet (Gecko Press), starting with the multiple award-winning The Travelling Restaurant. She also works as a manuscript assessor.