Crossing to surgery’s side

By Jane Simpson | Posted: Monday Oct 07, 2019

Months after a serious accident, despite doing all the prescribed exercises, my right shoulder was getting worse. Simple movements caused sharp pain. Physios continued to hold out the hope of healing for this ‘small’ tear of my rotator cuff. I doubted that it would repair and said I wanted surgery. The path seemed to be blocked.

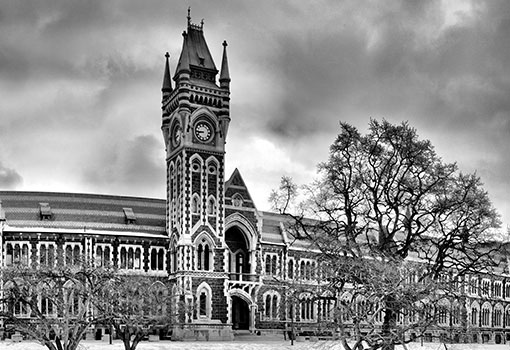

What I had waited so many months for became imminent at the second appointment with the surgeon. An MRI showed that the rotator cuff damage was much more serious than expected, and so he brought the date of surgery forward by two months. As I passed back through the spacious reception area, its white walls with their innocuous paintings suddenly became huge shadow boards of clamps, hammers, saws and numerous surgical instruments – like the ‘Cut Outs’ series by the New Zealand artist Richard Killeen.

What was I afraid of? Fear of surgery, of it all going wrong? If I were to write a poem about fear, what verbs, metaphors and myths would I use? Could I use synaesthesia and mix the senses up? If so, what was the smell of fear, what was its taste? Metallic?

Nine months after the operation, I was ready to face writing about this. Now I had to enter fear’s territory. ‘Crossing to surgery’s side’ is one of the last poems I wrote in a manuscript called ‘Dress rehearsal for old age’ which I had started only two weeks before surgery. ‘Crossing to surgery’s side’ proved to be the most difficult poem to write. As I wrote and rewrote, the image of Charon came to mind, the terrifying ferryman of Greek mythology who carried the souls of the dead across the rivers Styx and Acheron to Hades. The payment he demanded was a coin, held in the mouth of the newly deceased. I was battling to get across something to the unknown. What I wanted to say seemed at once obvious and crazy. As an academic, I shrank from both. As a poet and religious historian, I also knew the power of myth and the hold that fear has over us.

As I kept wrestling with the poem I realised that my deepest fear had not been of surgery itself, but of the time immediately afterwards when my shoulder and arm would be immobilised in a sling. I wouldn’t be able to write; I couldn’t imagine not writing. Perhaps I could type with my left hand but that might cause jarring pain. Dictating with voice recognition software seemed a solution. I had used this in historical research, but writing poetry requires something more intuitive, that most intimate of ‘instruments’, the hand. It was then that I remembered a conversation with the surgeon. I had said, “If I can’t write, I’ll burst.” He had laughed, a rare laugh of surprise and respect, then scribbled as if from inside a sling: these tiny movements would be safe. A month after surgery I read a doctoral thesis which rested on a pillow while I look notes in very small, legible writing, my arm in its supportive sling. That is another poem.

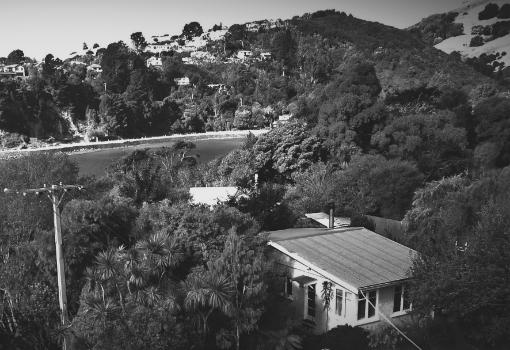

I realised that I had longed for surgery more than I had feared it. With that realisation came an image of surgery personified as an unreachable Greek god, reclining on a distant shore – indeed, forming the shore. I instantly thought of Picasso’s wonderfully spare etchings of figures from antiquity in his Vollard Suite (1933).

In ‘Crossing to surgery’s side’, I conquer fear, go to surgery’s side, visit the underworld and come back with the gods to the land of the living. The poem subverts the myth and robs fear of its power.

This is one of a number of poems that explore themes I never thought I would need to write about: incapacity following a serious accident, the work of medical professionals, the longed-for surgery and the period of recovery in which I faced my fears as a writer. These themes are universal and also very particular. I would like my manuscript to be used by medical students, giving them a much-needed patient perspective, integrated with themes from art and literature (see contact email below).

Crossing to surgery’s side

The physio knows each patient’s lexicon of pain,

but puts numbers into their mouth. How bad must it be

– 8 out of 10 – to be referred to surgery’s side?

The specialist holds a syringe of cortisone,

a needle of hope; bullies me out of the shoulder repair.

Where is there to go, if not to surgery’s side?

The orthopaedic nurse next door

bales me up in the street – it’s all a conspiracy.

Who will clear the way to surgery’s side?

The taste of fear is the coin in my mouth.

Old Charon looks with feverish eyes.

Will he ferry me across to surgery’s side?

The date is fixed. His skiff is ready – the colour of rust.

He is entranced by my mouth – lets slip his oar:

I will row across the Styx to surgery’s side.

There two nights, months too late for any repair, but justified,

god-like, I return – my life given back, on surgery’s side.