Landfall Review Online

By Landfall Review Online | Posted: Monday Nov 30, 2020

Reviews by Piet Nieuwland

Enduring Love: Collected poemsby Robert McLean (Cold Hub Press, 2020), 220pp., $40; How to be Happy Though Human: New and selected poems by Kate Camp (Victoria University Press, 2020), 160pp., $30; Yellow Moon/E Marama Rengarenga: Selected poems by Mary Maringikura Campbell (HeadworX, 2020), 84 pp., $25; New Transgender Blockbusters by Oscar Upperton (Victoria University Press, 2020), 72 pp., $25.00

At first glance, Enduring Love by Robert McLean feels like it’s going to take me places I’ve never been before. There are new references, and suggested connections to lives and events that seem peripheral and obscure.I am curious. If I keep Google on hand I will at least be in the park, if not in this particular game—it’s modernist with rhyme, not usually me, but here goes.

‘For Renato Curcio’ is my favourite of this collection. It reminds me of the time I spent in Italy shortly before the kidnapping of Aldo Moro, and the passionate questioning of the right way to live during that time. It’s also a refreshing reminder of the positive energy of late 1970s Christchurch. I was living there at the time; this poem resonates. There are references galore to the historical events around the activities of the Italian ‘Le Brigatista Rosse’, including a poignant line:

… One man’s freedom fighter may

be a terrorist to

the Other. O… such is wisdom

Surely that anger, frustration and sense of oppressed helplessness are sentiments held today, when our most potent tool, social media, is levelled against us.

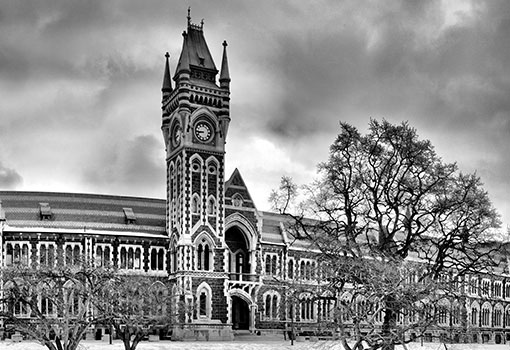

In the next series of poems, set in Canterbury and North Otago, we are taken moment by moment on a walk through Hagley Park; sitting on a veranda on a rainy morning; and ending up in Ōamaru with a view of the beach. These poems are each finely carved from the poet’s lived experiences of the city and coast.

‘For the coalition dead’ reminds us of the humanity of soldiers, with a sense of theatricality. The futility of death is described as a matter of fact in the first verse; what follows are flashbacks to Mexico, learning to shoot with your father, bibles on the White House lawn, the unique flavour of charred bone. The absurdity somehow makes sense—no, actually, it doesn’t: it is lunacy.

If the aforementioned poems sound unexpected and abrupt, there are othersthat feel more relaxed and rhythmical. In ‘A graveyard by the sea’, for example, we are taken from a peaceful description of Rāpaki Beach to the disruption of earthquakes and the First World War; the poem concludes with an image of a yacht sailing: all is motion, life goes on. Fair sentiments, but the long, rhyming sequences feel indulgent and overdone.

The poems in the section ‘Figure and Ground’ feel uneven, and the rhyme is a distraction. The best are those with a definite person or place, such as ‘In memory of Anne Sexton’ or ‘A view of the Canterbury Plains’. The latter, a memorial to Colin McCahon, concludes with a nod to Baxter. ‘Goldfinch and hawk’ is a concise and direct expression of the poet’s love for his wife. In ‘Housekeeping’, the structure of the rhyme fits the subject of the poem.

The final section takes the reader to another century inboth style and subject matter. Pieces such as ‘At the Rakaia, Lake Coleridge Basin’ are tight and dense with a clear point—I can see the view from here. And with ‘At the Sign of the Packhorse I stand like a tree and sing my song of joy’, I am glad to have been transported along the path of this poet. It’s not always easy going, but after I moved through the nuances, dalliances and passions set down here, I finished this book with eyes opened.

The weight of reputation bears heavily on Kate Camp’s new book, How to Be Happy Though Human: New and selected poems, in which we are asked to take the advice, swallow the pill and acknowledge the failings of our humanity.

Here are sixteen new poems and a selection of work from Camp’s previous six collections. Camp is an award-winning poet, with, for example, the 2011 Creative New Zealand Berlin Writers’ Residency and the 2017 Katherine Mansfield Menton Fellowship to her credit. This book is published simultaneously in New Zealand by Victoria University Pressand in Canada by the House of Anansi Press—which probably explains the curious statements on the back cover about North America, and Stephanie Burt yelling at North Americans about what to read.

The poems say what they say in an often amusing but straightforward way. Take, for example, the poem that gives the collection its title: ‘How to be happy though human’. After seeing a film

… where three people taxidermied a baby zebra

caught in the moment of standing

for the first time.

we return to the human thing:

we dance with other people

other people’s children,

create community with physics

This poem concludes with:

Memory is a kind of mourning.

We take each other’s hands

as if they were made for that

and we form a circle.

There we have it—the secret’s out.

The next few poems move the reader through the details of the rooms of houses. In ‘Baffin Island’ Camp recalls her childhood experiences of living in different houses, and a National Geographic map of Baffin Island that decorated the toilet wall—a symbol of endless childhood fascination and a stimulus to imagination. As a child I also loved those maps with a passionate curiosity. This sense of curiosity works its way into ‘Beach house’, too, with its image of a house being moved on a truck.Camp navigates further through her home in the dark, past interior geographies of Monument Valley and eventually to the moon itself. The reader is drawn in—images transposed from National Geographic to a child’s mind to a poet’s page.

The remainder (and bulk) of the book is made up of a selection of poems from each of Camp’s earlier collections.They trace the last two decades, showing transitions in subject and emphasis but with her characteristic quirky eye and personal touch.These are poems that are engaging, enjoyable and mostly easy to relate to.They are also a reminder of my own experiences and memories of those decades—Camp has a way of connecting to the reader.

A few favourites stand out for me: ‘Lazy eyes’, with its sudden realisation of the meaning of a word; ‘To tell myself seven stories about me and you’, fragmentary accounts of a relationship;‘Water of the sweet life’—who hasn’t thought that?; ‘Driving the bypass’, after leaving the hospital to take care of a loved one; and ‘There is no easy way’, with this memorable line: ‘you will always be inside things’.

This is a varied and engaging selection of Kate Camp’s poetry, and I recommend it as a place to get to know her, if you don’t already. Although you will still be human, you will no doubt be happier.

While Camp’s title had an immediate effect on me, the cover image and presentation of Mary Maringikura Campbell’s Yellow Moon/E Marama Rengarenga drew me to it. There is plenty of space in this book. The pages are clean and uncluttered. There is room for the reader to reflect and add these poems to the threads that make up their own life. And the title, especially E Marama Rengarenga, carries the weight of the author’s Tongareva ancestry, and the literary legacy of her parents.

The book’s first half comprises previously uncollected poems, from the 1970s to 2019. These are not poetry exercises, technical gymnastics or linguistic word plays. The poems speak from the heart to the people of her life, from her life, about the things that matter. They are serious, funny and relatable.

‘What the …’ is addressed to her cuz, warning of the potential consequences of suicide. ‘Ethel Mary’, too, is a sad lament for a close relative. ‘Imagine’ pays homage to the mothers of Porirua who are doing their best to feed, clothe and protect their children. We find Mary laughing with her husband, reflecting on failed job applications and questioning her friends about their intentions and real feelings. These are poems about humans and human relationships. The section concludes with longing for the simplicity of life and death in the Cook Islands.

The second section, titled ‘Maringi’, previously self-published and now reprinted, takes on similar themes and subjects but feels more assured. ‘Danish feet’ is funny with its consideration of which part of the poet is Danish. Experiences in a psychiatric hospital emerge with humour, as in ‘Arita’. ‘Tupuna (II)’subtly hints at the mystery of language and pronunciation of Cook Island Māori.

For me, this is a way of connecting lines to those islands that have come to us in Aotearoa; pieces that make us who we all are here. After all, we do see the same yellow moon over Moana Oceania.

With a title like New Transgender Blockbusters, Oscar Upperton’s first poetry collection suggests a grand scale: it sounds like a film—big screen, surround-sound, celebrity super-heroes saving the city, even the planet. And who knows—maybe that is to come. Oscar Upperton wants to change the world, and his first book begins with a declaration in ‘Atlas’:

… I am inverting.

I am inventing a new way to act.

There is a sense of theatricality, film and the other reality, a deep yearning for a different world where the ideals of the film are realised, where transgender people are included and accepted without question. And what better way to do that than to have lots of fun, to play, to lighten up, to gain some attention with serious amusement, to engage children? Here the ordinary world is reframed again and again. The poems are frequently grouped in pairs or triplets, where the first poem is counterpointed, explained, clarified or extended by the second and third. This is clear in ‘Yellow house’ and ‘Explaining yellow house’, where the second poem is composed of interpretations of the first.

In ‘Child’s first dictionary’ the meanings of phrases are explained in ways that Tess, to whom the poem is written, will no doubt appreciate more fully. In ‘Numbers’, then, we are given some alternative ways of describing quantifications that are easy for children—and adults—to relate to. Likewise in ‘Panic attack’, ‘This is a breathing exercise’ and ‘Allergy’, where we are taken through experiences of difficulty with breathing, where what emerges is a need to keep calm, relax, focus, concentrate—to be alive. This sense of restriction and confinement emerges throughout the book, such as in ‘Home sick’ with its repetitions of ‘The lead-lined red box that shuts with a twist’, and ‘Juggernaut’, which ends with ‘Is your house a bottle? Are you trapped in there?’

It’s not all fun, though. ‘Interrogation’ meditates on listening and the listener, the person—and the rooms of a building wired for surveillance. It asks what and how is education. It examines the nature of communication and understanding in the context of nuclear capability. And ‘Somebody to love’, the title of one poem, is revisited as a theme in the poem ‘3:06–4:54’—which shows a lonely call for intimacy, companionship or whatever counts for love in this reframed and inverted world.

Upperton has a way of linking the urgency of poetry to the urgency of being human. There is a lot more we need to do in order to work out how we relate to one another. The poem ‘Poetry exercises’ provides us with an almost limitless variety of starting points. And the four poems to four friends, titled ‘Dark night’, pull threads together, reminding us of key messages about the act of being human: it’s scary out there, stick together, be brave.

PIET NIEUWLAND has poems and flash fiction that appear in numerous print and online journals published in New Zealand, Australia, the United States, Canada and India. He is a performance poet, edits Fast Fibres Poetry and lives near Whangārei.