An incident in Millers Flat

Posted: Thursday Mar 21, 2024

Kyle Mewburn tells the story behind the house she bought after conducting the land transfer in Gore

An incident in Millers Flat (newsroom.co.nz)

On December 21, 1990, at 12.22pm, Kyle Mewburn, orchard worker of Ettrick, and Marion Mewburn, married woman of Ettrick, became the proud owners of 3 acres, 3 roods and 30 perches of windswept grass, being Section 27, Block XII in the Benger District. For which they paid the princely sum of $7000.

I should point out that Marion had also written “orchard worker” on the form we’d filled out at the lawyer’s office in Gore where the land transfer was conducted. We can only speculate why someone decided she should be recorded as “married woman” in perpetuity. Perhaps they were simply flummoxed by the notion we both wished to be recorded as owners on the Certificate of Title, breaking a long, all-male tradition stretching from Edgar Wilson, electrician of Mataura — the previous owner — all the way back to the original owner, Robert Ridd, retired farmer of Millers Flat.

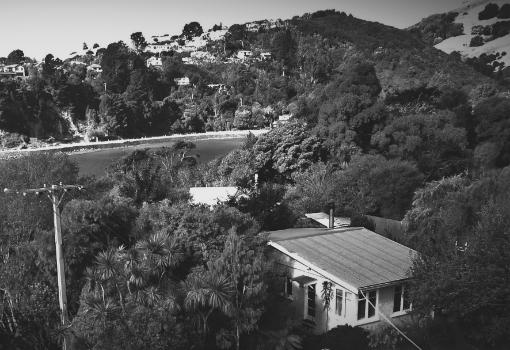

The land — a north-facing slope, dotted with schisty outcrops and bordered by the Minzion Burn — was zoned rural and considered undeveloped, so valued at a mere $3000. The corrugated iron shed inside the front gate was valued at $4000. A thousand dollars an acre was pretty much the going rate in the area at the time. The hitch, for young folk like us searching for an affordable place to live, was that most sections were well over 30 acres. There were only a handful of smaller sections in the valley. Ours was the only one without a house on it.

We naively imagined we could simply begin building a house on our property. But the local council had other ideas. Unless we could convince them our land was a “viable economic unit”, we wouldn’t be allowed to live there, for fear it might undermine the District Plan.

So we set about researching our section. Which mostly meant fishing stories from older locals, especially those of the area’s two unofficial historians: district nurse, Betty Adams, and the local Rabbit Board hunter, Geoff Thompson. Our new neighbours — give or take a kilometre or two.

We discovered our section was the last in a cluster of repatriation blocks — a string of similarly-sized sections created post-WW1 to be offered to returned servicemen. And that the first electricity in the valley had (possibly) been generated at the bottom of our section during the goldrush. There was certainly evidence to support this story, too — several rusted, twisted sheets of heavy steel sticking out from a collapsed bank; and a low concrete weir restraining the creek a few bends further up the hill. We also heard the first murder in Millers Flat, the infamous killing of a travelling salesman known as “Yorkie”, might just possibly have taken place in our bottom paddock, too.

Most importantly, and more relevant to our predicament at the time, we learnt there had once been a house on the section. Scant evidence of it remained. A graded square just inside the gate where the mystery house might once have stood. A concrete block upon which a wash-house might once have sat. Though we had no idea which of the previous owners had lived here, or anything more than hearsay to support our claim, it was sufficient to mount a successful case for an exemption to the District Plan.

Over the years, as I built our grass-roofed house, planted a macrocarpa hedge along the roadside border to shelter an orchard of heirloom fruit and nut trees, and dug my first garden, I’d regularly unearth traces of those who’d walked this land before me. An empty bottle of Baxter’s Lung Preserver. Bent horseshoe nails emaciated with oxidation. Large pieces of plough. A rust-encrusted buckle. In our upper paddock I found three decaying rounds of what must have been a sizeable tree, lying half-buried in the grass like fossilised dinosaur vertebrae.

Though there were stories under every stone, I never gave them much thought.

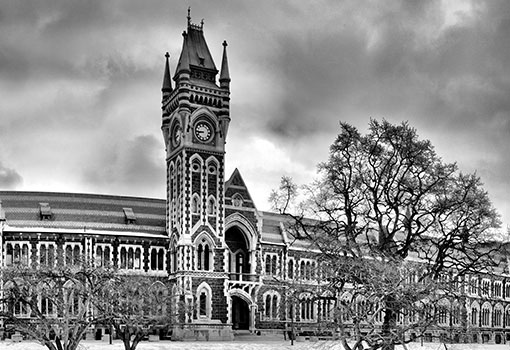

In 1997, I finally decided to give writing full-time a crack. A somewhat Quixotic decision to try my hand at freelance journalism had me idly sifting through rows of hardbacks at 3 a.m. during Dunedin’s Regent 24-hour book sale. As I chatted to a volunteer refilling the table, we quickly realised that our property had once belonged to her grandfather, Benjamin Waller.

From the Title, I knew he’d bought the section on December 3, 1927, before selling it to a local farmer in 1949. I also knew he’d discharged three mortgages on the property. They were the kind of dry, historical details that might suggest further paths of exploration to a genealogist, but hardly the kind of stuff to inspire a novel.

Luckily Kathryn, the volunteer, had a wealth of stories from the many memorable summers she and her sister had spent there as children. I was rather dismayed to hear the property had once been an oasis of gardens, orchards and perennial borders, all concealed behind a large macrocarpa hedge. After six years of hard slog, our oasis was still at least a decade away.

Kathryn also shared the story of her grandmother, Mary, whose family hadn’t been at all impressed with the notion of their daughter marrying a mere farm worker. At the wedding, they’d presented their stubborn daughter with a brand new Singer sewing machine — after which they never spoke to her again. The philosophy behind the gift being that a woman with a good sewing machine would never want for anything, as she’d have the wherewithal to provide most of her family’s needs.

In 1949, the house was destroyed by fire. The Wallers, who were approaching seventy, sold the property and moved away. Benjamin died two years later. I have no idea what became of Mary.

In the intervening years, almost every tree on the property had been felled, leaving no trace of the Wallers’ decades of toil, or of the joys and sorrows they undoubtedly experienced on their patch of paradise. Though this vandalism seems utterly pointless, and inestimably sad, there is also reason to be thankful. For had it been otherwise, it’s unlikely we could have afforded this place.

The Wallers’ story, and the notion that we are simply repeating a fleeting dance across this patch of land, was the starting inspiration for my novel, Sewing Moonlight. Though the novel’s context — New Zealand between world wars — is grounded in historical fact, coloured by copious research, many key incidents are loosely based on true stories garnered from local folklore. Much of the Wallers’ story may be mere hearsay. Family folklore. But I’ve never been one to let facts get in the way of a good story, and I’d like to think Benjamin and Mary would be pleased.

Sewing Moonlight by Kyle Mewburn (Bateman Books, $39.99) is available in bookstores nationwide from April 1.

Kyle Mewburn is one of New Zealand's most prolific writers. Her books include picture books (Old-Hu-hu; Hill & Hole), junior fiction series (Dinosaur Rescue; Dragon Knight), and her first novel for adults, Sewing Moonlight, published in 2024. Her titles have been translated into 18 languages and won numerous awards including Children's Book of the Year. After 25 years of hiding her true identity, Kyle told her wife Marion that she was transgender. With Marion’s support Kyle flew to Argentina for facial feminisation surgery. Her life story is poignantly described in her memoir Faking it: My life in transition.