Winner of the Sargeson Prize schools division

By Newsroom - Tunmise Adebowale | Posted:

A Nigerian girl and her Pākehā boyfriend at a swimming pool

Winner of the Sargeson Prize schools division (newsroom.co.nz)

Tunmise Adebowale, a Year 13 student at St Hilda’s Collegiate School in Dunedin, has won the Secondary Schools Division of the 2023 Sargeson Prize, for “The Catastrophe of Swimming”, described by judge Vincent O’Sullivan as a story about “a Nigerian girl and her Pākehā boyfriend at a swimming pool where young swimmers are variously on show, watching and hoping to be watched”

I fix my gaze on the pole on the other side of the swimming pool instead of focusing on my boyfriend or the girl he’s watching. The plant that sits near the fence separating the pool from the parking lot is weirdly shaped so I give it a glance, feigning amusement at the oblique curve of its branches. I read aloud the rules for the pool restrictions from the entry sign: ‘No eating or drinking in the pool water’ and ‘No running in the pool area.’ See? I made a joke. This distracts my boyfriend momentarily. He chuckles and reaches across the little space between our deck chairs to grasp my wrist. When he rests his head against the back of his chair and turns to watch the girl again, I don’t follow his stare. I don’t pretend to clear my throat or sneeze. I don’t say, “Stop it.”

The sun is shining, even glittering over the surface of the water. I admire the scenery while quietly humming to myself. I cast a glimpse behind my boyfriend’s head, which has turned away from me and towards the girl. I stroke the back of his neck with my fingertips. He tilts his head, my palm against his mouth, and kisses the back of my hand. As he pulls my chair closer to me, he merely glances at me. I convince myself that he loves me because he truly does.

But I take a look at her. I stare though my sunglasses, which I have slipped down the bridge of my nose. I glance through the strewn deck chairs, beach towels, and sandals on the sidewalk to the girl sitting in a red bikini along the edge of the pool, swinging her legs back and forth in the water. White cheeks, white shoulders and white thighs. It’s difficult to not see her as I imagine my boyfriend sees her: her hair streaming down the valley between her shoulder blades and lifting each one with grace. She smiles as her friends splash and play in the water, an effortless grin that does not tremble with uncertainty as I imagine my smile sometimes does. Blissful, she is. A light beam that gathers on earth.

My boyfriend does not stop looking. I can’t blame him; she’s gorgeous. But he’s crossing a line. “How about Wellington for our next trip?” I ask. “We could try sushi again for dinner tonight,” I suggest. I don’t say, “Please stop.”

I remind myself that he moved from Australia to become my boyfriend (I will later feign amusement when he tells me it was my culture that made him look). I recall him hugging my body against his to keep me from walking out after arguments. I recall how closely he holds me when we fall asleep together, and how he always reaches for my hand under the moonlight. He’s chosen me. He holds on. So what if he occasionally stares at other girls?

I’m afraid now because he’s staring at her with such conviction, devoted attention, that she feels his gaze and turns. Their eyes are locked on each other. They’re now in each other’s lives. For a brief moment, they are dedicated to one other. The girl starts moving for him, arching her back, running her fingers through her damp hair, rotating her head so the blond falls over her shoulder, then towelling it. This is intended for him. He knows and watches.

I feel sick. I take a sip of my Coke. Ignoring the avalanche in my stomach and the guilt I believe I’ll feel later that night when he kisses me and opens his eyes and is disappointed to see me instead of her. I take another sip, wishing he’d quit staring.

I tell myself that he loves it when my brown skin deepens to chestnut in the sun. I tell myself that he likes the way my coils and curls cling to his fingers as he runs them through my ebony hair. He adores the thickness of my lips and thighs. I’m starting to forgive him since he can’t possibly understand why watching her is violent. He has never met the young girl I once was, born to a Nigerian father and mother, but who grew up surrounded by foreigners. He’ll never know the young girl who looked into her teacher’s blue eyes and wondered when her own eyes would lighten and her skin would grow pale, allowing her to be like the other girls and receive affection. He’s never heard her classmates make fun of her complexion because it doesn’t match the ‘skin-colour’ pencil. He’s never seen the little girl standing in front of the mirror, wondering how much bleach lotions and hair straighteners she will need to tame her. He hasn’t seen the white Barbie dolls in her childhood. He has no concept of how difficult it is to keep that tormented girl silent.

I wonder what would happen if I told him about the connections. But moments like this have defined my existence, times of being eclipsed, and nothing I’ve ever said or done has diverted anyone’s gaze away from the light to see me in the dark. I’ve discovered how much safer it is to pretend. So I put on a fake smile and talk about the weather. I pretend that the tree branch is more intriguing than the blond hair that my boyfriend’s eyes have landed on.

I want to reclaim his focus, but what usually works doesn’t work today; pointing my toes to stretch my legs (hers are longer), running my fingers down my thick thighs (hers are slender), pouting my big lips (hers are lean). I coax him into the pool. He comes. I wrap my legs around his waist and pull him closer after he’s in the water. I raise my head, allowing the sun to reflect in my dark eyes. I’m not going under the water. Two things will happen if I do. One, my boyfriend will most likely use those moments to examine the girl again. Two, and this is much worse, as I come up for air, my afro will wither and shrivel. And my boyfriend might stare at the girl again, oblivious to my presence, and notice the lovely blond hair falling down her back.

The girl makes her way, swimming towards me and the boy I love. This girl is so sure of herself, so sure of him she doesn’t care.

“She’s coming,” I inform my boyfriend. He remembers me now. He senses me again. He grabs my hand in his and I glide down the cool water behind him as he leads me to the other side of the pool. He cradles me in his arms, turns his back to the girl, kisses my shoulder.

“I like how the sun shines and sparkles on your skin,” he says. “It loves you almost as much as I do.”

He probably thinks I’ve only just noticed him watching her. He believes he’s concealed it well. I want to scream but I pretend nothing has happened. I’m good at that.

Colonisation has that effect.

The girl stops swimming. She treads the water, watching me with pale eyes glowering then scanning my boyfriend’s back. I keep my eyes on him and rub my nose against his. I laugh. She needs to know she hasn’t made a difference. I need to show it.

My boyfriend kisses me, cradles my back, runs his lips across my collarbone. He says, “Wellington would be nice.” He says, “I’m not in the mood for sushi.” I should tell him it’s what I want. Whether he realises it or not, he owes me now.

I watch carefully as my boyfriend climbs out of the pool and returns to his deck chair, drops onto the chair and wipes his face with a towel. He is no longer looking at her. Instead, he reads a book, tans and takes a nap. He doesn’t notice the girl as she passes. He’s returned to me. It’s all over now. Breathe.

I swim a few laps to relieve the pressure in the centre of my chest so it doesn’t drag me to the bottom of this pool. I linger in the water. I let the sun dry the water off my shoulders and face because I enjoy the sensation. I inhale the fresh, cold aroma of chlorine, as well as the sound of water and the smooth streams flowing between my legs. I adore water. I’ve adored it since I was a child and discovered that if I stayed, the water would warm me. What was challenging was learning to float. I learnt I could either brace my body against the surface and sink, or relax and let the water carry me.

I lift my toes from the bottom of the pool. Float onto my back. And spread my limbs out like a star.

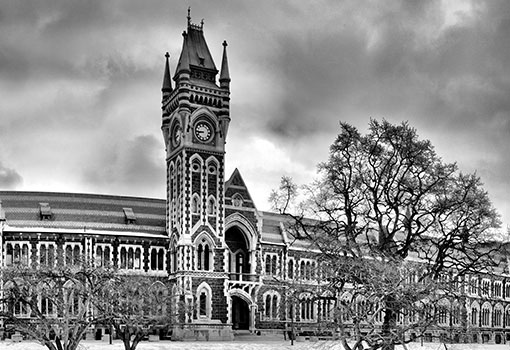

The Sargeson Prize, the richest short story prize in New Zealand, is staged by the University of Waikato. “Pig Hunting” by Anna Woods won first place (and $10,000) in the open division,“On Beauty” by Jake Arthur was judged second, and “Apple Wine” by Claire Gray was third place. As winner of the 2023 schools division, Tunmise Adebowale adds the prize to her win at this year’s 2023 Poetry Aotearoa Yearbook poetry competition for the Year 13 category.