The stories that got bookworm Tony Eyre hooked

By The Post | Posted:

Tony Eyre is a book lover. Now, he is a book writer. His bibliomemoir, The Book Collector, tells the story of a lifetime devotion to reading, books and their authors. In this extract, he shares the stories that sparked the joy.

View Original Article with Images Here: The stories that got bookworm Tony Eyre hooked | The Post

For the first time, in that transition from Avondale to Marist Convent School in Mt Albert, the pleasure of books entered my consciousness. My earliest memories are the Janet and John books. The very first reader, Here We Go, with its bright yellow and red cover of Janet and John floating on an inflatable horse is vivid in my mind. In another, I Went Walking, the jaunty skip-along wordplay set me on the path to read. ‘I walked, and I walked and what did I see? I saw John and John saw me.’

In the collection, Through the Garden Gate, I remember the tale of Chicken-Licken, and being entranced when Chick-Licken, bopped on the head with a falling acorn, decided to go and tell the king that the sky had fallen in. There was no happy-ever-after in the terrible finale where Fox-Lox lures the gullible chicken and her poultry friends into his ‘shortcut’ lair where, with the help of his cubs, he greedily gobbles them up.

As my reading levels improved, the more advanced hardbacks in the Janet and John series, like Once Upon a Time, introduced me to the primary school classics, Little Peachling, The Three Billy Goats Gruff and the exotic Aladdin and his magic lamp.

My childhood love of books had begun with the filled pillow slip at the end of my bottom bunk on Christmas morning. Christmas was not always a happy time in our household. As the festive season approached, a gloom would often descend over my father, and he would stay in bed all day rather than join us for Christmas dinner or share in the opening of presents.

At worst, there were no gifts to put in our empty pillow slips. Once, at my father’s beckoning from his bed, my hand would produce a few coins from the pocket of his trousers hung over the back of the bedside chair, to be placed into the pillow slips of my younger siblings.

But in happier times my father overcame his Christmas malaise and took pleasure in buying me books for the occasion.

Enid Blyton’s Famous Five stories with the adventurous Julian, Anne, Dick, George and Timmy the dog dominated the young readers’ book market. Five Go to Smuggler’s Top and Five Go to Mystery Moor were favourite titles with their air of mystery. The ubiquitous Biggles, whether he was in Africa, the Gobi, the Orient, the South Seas or in the jungle, also captured my imagination.

There is one book, Thomas Hughes’ Tom Brown’s Schooldays, a Christmas present from my father in 1964, that holds a special place in my affection. It is significant because I know he made a special effort to visit J.H. Bigelow’s Bookshop in Shortland Street, Auckland to find a book that had delighted him as a child and to it share with me. This green clothbound illustrated edition with its bright orange dust jacket is the only book gift from my father still in my possession.

Tom Brown’s Schooldays was the first I ever owned in this collection of over 300, redesigned and reissued as the Collins New Classics series in the 1950s. The pen and ink drawing on the dust jacket depicted the headmaster, Dr Arnold, with a handkerchief over his nose to contain the horrid stinks from chemical experiments emanating from Madman Martin’s study. As an eleven-year-old schoolboy, it was a story I could relate to, despite it being set in a 19th century English boarding school.

I was already reading comics for boys like Lion, Tiger, The Victor and the more compact War and Commando, ordered weekly from the local book and stationery shop.

Another satisfying read was the Look and Learn, an English weekly educational magazine, beautifully illustrated in colour, its contents delighting my growing thirst for knowledge.

I had also discovered the colourful Classics Illustrated, with their striking cover designs, which had me reading adapted literary classics in comic book form. Intriguing titles like A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, The Man in the Iron Mask and The Prisoner of Zenda alongside Jane Eyre, Moby Dick and Lorna Doone were soon purchased by me, one by one.

You could build your own library by ordering a binder overseas, embossed with gold lettering, to hold your first collection of comics.

This I did with my ten-shilling postal note enclosed, only to have the letter returned, address unknown.

Disappointedly, I had left the street name out of the London address. My collection never survived ‒ coins, postage stamps and matchbox labels became the new collectibles.

A couple of years ago, I popped into a Dunedin comic shop, Waypoint Comics, and to my surprise, found Classics Illustrated original comics for sale. Indulging in a bit of childhood nostalgia, I walked out with number 95 in its protective plastic sleeve – the comic publication of Erich Maria Remarque’s anti-war classic, All Quiet on the Western Front.

Talking of comics, my son Danny, when he was younger, had a passionate interest in the multi-genre science fiction world of Star Wars. Cutting his teeth writing for the online encyclopedia Wookieepedia, he eventually assisted with research for Star Wars: The Essential Atlas, published in 2009 by Random House.

As an avid collector of early Star Wars titles published by Marvel Comics, he asked me to look out for one or two at an upcoming Dunedin auction where a collector was disposing of his lifetime collection of science fiction ephemera.

The boyhood comic collector in me must have emerged, for I successfully bid and brought home multiple boxes of Star Wars comics, magazines and annuals (doubles and even triples included) much to his shock and delight. He gladly accepted them, but not the bill.

When I reflect on my interest in reading, I realise we were lucky to live in a home full of books.

With five children, our parents did their best to provide us with what they saw as educational books to support our school learning. Reader’s Digest publications like Great World Atlas and Great Lives, Great Deeds, were well-thumbed publications, and the brightly coloured sixteen-volume Golden Book Encyclopedia with its distinctly American focus, was a core part of the home library.

I can’t recall my parents ever reading novels when we were young, although my father, who was born in 1907, did often fondly recall his childhood favourite – Harry Leon Wilson’s humorous Ruggles of Red Gap, first published in 1915 and made popular in three later movie versions.

What did fill our bookshelves was New Zealand non-fiction titles reflecting my father’s interests – the kauri timber industry, ferry boats on the Waitemata, the coastal shipping trade, Auckland’s tall-masted scows, and art books like Peter McIntyre’s New Zealand – mostly published by A.H. & A.W. Reed.

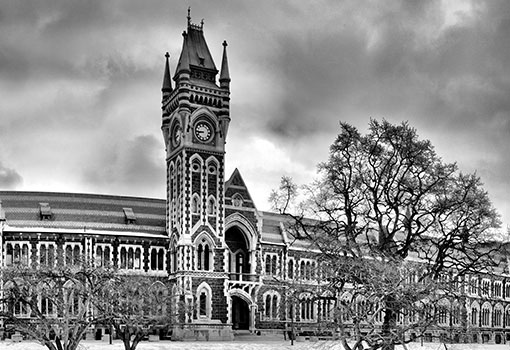

In 1912, Alfred Reed and his wife Isabel moved what was their Sunday School Supply Stores business onto the top floor of the New Zealand Express Company building in Dunedin, proudly referred to by Reed as the Dunedin skyscraper, being the tallest in the country when it was built in 1908. Here the business occupied two large rooms which, coincidentally, became part of my own business premises more than 80 years later.

Ornate bookplates were a product that A.H. Reed supplied to Sunday Schools in the 1920s onwards for affixing to children’s book prizes. I have come across lovely examples of these. A favourite one features a kiwi, cabbage trees and ferns, bordered by a red and black kowhaiwhai (Māori motif ).

This was in a book awarded in 1934 to a child for second prize in Catechism at the Tokomairiro Presbyterian Sunday School in Milton.

Book presentations at end-of-year prize-givings were a feature of my primary schooling and I do recall getting the odd one, but no titles come to mind. Books for boys were chosen along traditional gender lines and a frontrunner was the Biggles series of adventure stories.

The Book Collector: Reading and Living with Literature by Tony Eyre is out now