A river runs through him

By Stuff.co.nz | Posted:

We only truly know one river in our lives. US writer Thomas McGuane said so and even this struck him as too expansive. So he added: only one part of that river would we know intimately.

New Zealand fly fisher Dougal Rillstone realised he wanted more than that.

He wanted to clarify to expand, to better understand his river. The Mataura.

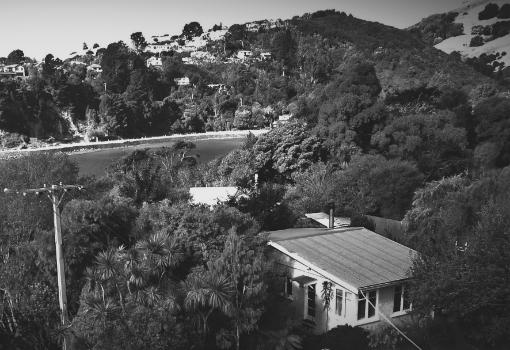

So Rillstone, who is in his 70s, headed off on a 240km walk following it from sea to source, the Fortrose coast to the Eyre mountains.

Ace angler that he is, he left his gear behind for once.

Because he wanted to keep his head up.

His book, Upstream on the Mataura, is a rare thing. Past and present converge in writing that's topical and elegiac; redolent with memories, alive to new experiences, vibrant in sensory observation, and communicated in a way that has drawn praise from poets Kevin Ireland and Brian Turner.

As it happens, those two number among his outdoorsy buddies. But that’s less a disclosure of bias than an indication of Rillstone’s sheer companionability.

Which is just as well because this is such a personal story. And although he’s a man who knows his way around a yarn the book is as much a meditation as an adventure.

He writes of looking ahead to the Hokonui Hills and how, once he overcame the maddening slowness of it, he took pleasure in the subtle changes of light and shadow on the land.

I smelt the land: the odours given off when rain begins to fall on dry country; the sweet sourness of silage; acrid cow shit; a hint of clover honey; wood smoke; damp sheep’s wool; and the hard-to-define smell of the river itself, something that remained a constant – as though its essence wasn’t gathered as it went but instead lay somewhere high up in the peaks where it starts. I heard the changing song of the river . . . .

In case it doesn’t go without saying, there’s not a whole hell of a lot in here about how to catch fish, even though the Gore-born Rillstone does know plenty about that. In 1999 he was individual champion at the Oceania Fly Fishing Championships.

Cut the personal stuff, some initially-aroused publishers told him. You’re not that well known. There’s a big international market out there.

He knew what they meant. He’d read a lot of those technique-rich books himself but during the past two or three decades they’d turned stale for him. He also knew, from rich experience, that when people took to the river there was more going on than developing techniques for educated extractions.

Speaking by phone he recalls: “I’ve long regretted people hadn’t, 50 or 70 years before me, written about their feelings about the river and what it meant to them.’’

His story isn't a polemic about how wonderful the Mataura used to be and how degraded it is now.

For one thing, we don’t want to kid ourselves about the past. He has a photo of his first dip – a baptism, really – as a youngster safe in his father’s care. The swimming, the eeling, the dawning delights of fishing all emerge vividly from his memories. But so do the carelessness of the time.

As a boy, he’d love spending time at his uncle Ray’s Mataura bookshop (his cousin is Gore Mayor Tracy Hicks). It was just one of the early morning jobs to take the rubbish to the Mataura bridge and chuck in.

The river smelt bad then. A few hundred metres upstream of the bridge a series of pipes disgorged blood and all manner of stinking animal waste from the freezing works, along with the odd load of discarded paper pulp from the paper. It is little wonder that the shopkeepers saw no reason to treat the river with respect, because its desecration had already taken place.

To be sure he finds reasons for present-day sorrow or reproach. From rising nitrate levels in the groundwater and river from more intensive farming, small streams slowly choking with weed, to neglected opportunities for native planting in the fenced-off riparian strips, to bloody stock still getting into the bloody river, he bears witness to it all.

And yet he found that in many ways the Mataura looked as good now as he could recall. Running clear, the bottom is clean, even downstream of Mataura township, where it was in such bad shape.

Much of the abiding problem has to do with scale rather than scorn, he reckons. Most individual farmers look like they’re trying to do the right thing, but the overall impact is still the problem.

“I accept the great bulk of them do care and are not trying to do bad things,’’ he says. “They feel hurt when the finger gets pointed at them. It’s the big changes taking place in agriculture, driven by forces way outside New Zealand – this drive for efficiency and prices, in real terms, coming down.

‘’The proportion of our incomes we’re prepared to spend on food has come down dramatically and that’s pushed people to put more demands on the land.’’

This is Rillstone in conversation, remember. As a writer he’s averse to stridency, careful never to hector.

And encouragements abound. Time and again he’s struck to the cleansing power of rivers that can, given half a chance, recover from mistreatment.

Social change emerges too. Aside from disarmingly passages in which he takes his own grandchildren riverside, the sense of youthful experience is almost all nostalgic. Nowadays he mostly found himself meeting retired white men, most of whom got into fishing when the world was different for younger people.

These days I can easily go a season without seeing a teenager on the river.

As he travels the riverside, Rillstone recollects a great deal hard-case humanity. He forays into communities – hence the story of the male stripper seeking escape from het-up patrons after performing at the Croydon Lodge.

And from his innocent youth he recalls taking literally a story in the Mataura Ensign describing the delicate treatment needed by a man an eel had bitten on what the paper, showing a little euphemistic delicacy itself, chose to describe with less than biological accuracy as “his big toe’’.

Near Cattle Flat he encounters the possie where the local cop would take the police car down to the river, leave it on the flood bank with the door open so he could hear the radio, and plonk himself down in his uniform to spend the season’s opening morning worm-fishing.

Lesson being: “World would be a better place if more cops took up fishing.’’

There’s a dope grower out there who would agree; a friend of Rillstone’s who may be the only person in New Zealand to have landed a trout while under arrest.

Dobbed in by a pair of anglers, he was duly collared and while walking out to the road with a couple of policemen for company, spotted a trout rising steadily. His appeals for just one cast were granted and he landed his fly inches from its snout. Success. A magical moment of fishing, though the officers didn't consider it an act of grace sufficient to let him off.

And so it goes, merry tales combined with tender accounts of fishing with a dying friend, of trips taken because there’s lifechanging news to impart and, well, where better to do it? It’s easier to talk about the things that matter when you’re away from it all.

By the time the story has made its way to the upper reaches, once protected from overuse by poor roads and distance, now inundated by fly fishers via the international airport up the road, we’re ready for a few summaries including the exquisite mini-essay titled “Why I fish.’’

Casting a fly gives me a chance to see this world, because to fly fish well you need to find a way to enter this natural place, not loudly at the top of the food chain but quietly, somewhere in the middle of it, connected to it by the fly attached to a leader, a fly line and a rod.

Not a bad place to understand the complex harmony of things.

Question arises; could this book have been written about, say, a mountain?

Rillstone considers a moment. Mountain writing tends to involve more excitement and danger, but the best of it, as he recalls, also finds the beauty that’s there in any natural place. Maybe there’s less drama around a fishing river, or maybe it’s more a slow-dawning sort.

“The cycle of water is such a miraculous thing. You can't walk up a river and watch this constant flow of water coming at you without being astonished, really, at the beauty, and the extraordinary nature, of this cycle that keeps perpetuating itself.’’

The longer you spend there, the more time to savour the sheer connectivity of it all. Including, it turns out, the friendships.

“I still derive enormous enjoyment out of it. Plenty of people reach the point in life, not far from my age, where everything past was so much better and they have lost that sense of enjoyment. I still feel like I’m a kid when I get near that river. It’s fantastic. Shouldn’t be allowed.’’

Upstream on the Mataura is published by Mary Egan Publishing.

https://www.stuff.co.nz/entertainment/books/123457819/a-river-runs-through-him