Dr Smith of Rawene

By Jocelyn Harris | Posted:

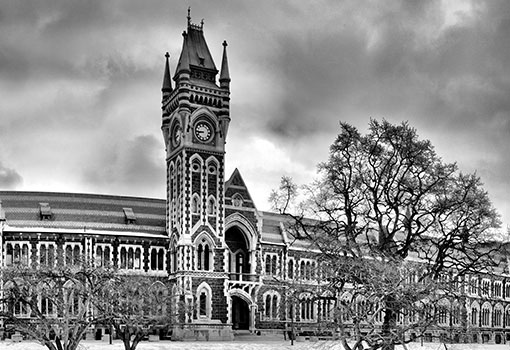

Soon after the war, my intrepid mother Margot Wood (later Ross) set off on the long, dusty journey from Dunedin, in the south of New Zealand’s South Island, to the Hokianga, in the far north of the North Island, in her little Ford Anglia car. My father, Captain Win Wood, had died in Egypt, and medical student Janet Smith, daughter of Dr. Smith of Rawene, was then our boarder. She would prove a life-long friend to Margot and a second mother to me. We were both run-down and thin, so Janet recommended a holiday with her parents, George and Lucy Smith. George was the well-known Rawene-based doctor George Marshall McCall Smith (1882–1958), described by the poet A. R. D. Fairburn as “a cross between an Arab Chieftain and an Archbishop.” To a small child, he seemed almost as awe-inspiring as Tāne Mahuta, for he was a tall man-tree with fierce, penetrating blue eyes, big hooked nose, white eldritch locks, open-necked white shirt, loose flannel jacket and trousers, flapping oilskin coat, old grey felt hat with a sagging brim, Roman sandals, and curved Cherrywood pipe. He and Lucy immediately set about stuffing us with fresh eggs, cream, and butter. Alas, I’ve never looked back.

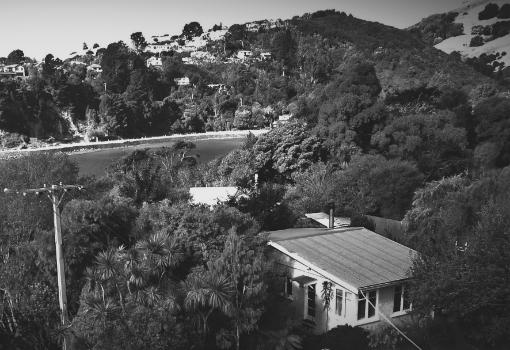

I remember waka racing on the harbour, and Māori children, blinded in a measles outbreak, singing in a choir. Rooms opening off the verandah were filled with flowers; sofas were strewn with books and journals; paintings by Olivia Spencer-Bowers and Eric Lee-Smith hung on the walls. We began to heal.

Appointed in 1914 as superintendent of Rawene Hospital, Smith demanded that the Hokianga Hospital and Charitable Aid Board pay for the very necessary improvements. The large Māori population was suspicious of Pākehā medicine, even though they were gravely in need of health services. But Smith proved himself in the influenza epidemic of 1918 when he ordered shops to close, posted armed men at crossroads to enforce quarantine, and organised teams to feed the sick. It worked.

Smith made nurses wear gowns, masks, and gloves to prevent cross-infection. He berated the conservatism of doctors, turned cod-liver oil and Vaseline into non-stick dressings, invented newspaper casts for simple fractures, placed a ‘black box’ over the head of an anaesthetised patient to raise CO2 levels, refuted the need to eat green vegetables, introduced painless childbirth, rejected circumcision, and encouraged schools to serve sheep’s-head broth to children. Unofficially, too, he raised money for equipment by means of a ‘hut tax’ on every house, an illegal casino, and an equally illegal raffle.

In 1921, the Board grew tired of his demands, but the locals rallied to prevent his dismissal. In 1928, he built a new hospital; in the thirties he published books and pamphlets supporting the Labour government’s policy for a state-funded medical service. In September 1941 he set up a Special Medical Area, a fully-integrated health scheme whereby the Health Board paid full salaries to doctors. Like the nurses, they travelled up the farthest reaches of the harbour by horse and by boat to diagnose and to treat.

Women flocked to Rawene Hospital to give birth without pain. As blogger ‘Island Ashley‘ puts it in a discussion of a book about Smith, Doctor Smith: Hokianga’s King of the North, by G. Kemble Welch (Blackwood and Janet Paul, Auckland and Hamilton, 1965), this Edinburgh-trained doctor “exasperat[ed] nearly everyone with his bombast, delivering babies while their mothers drifted in the the twilight-sleep of nembutal, doing his darnedest to improve the living standards and health of Hokianga people, and helping to establish the Special Medical Area designation for Hokianga that still remains in effect today.” She calls it a “pocket of completely socialized healthcare.”

In 1991, the Department of Health attempted to downgrade the Special Medical Area, prompting the formation of the Hokianga Action Committee. Janet Smith, now Dr. Irwin, and director of the University of Queensland Student Health Service, surged over the Tasman to help save her father’s legacy. The clincher, she said later, was that the free health service cost the government less per head than the paid service elsewhere, prevention being better than cure. Thanks to “one of the most impressive and successful grass roots political campaigns for health ever seen in New Zealand,” the Hokianga Health Enterprise Trust still functions independently as an advocate for low costs, accessible consultations, fresh air, good diet, and healthy housing. The Dr G. M. Smith Medical Scholarship for medical students with connections to Hokianga, administered by the Trust, commemorates Smith’s service.

Dr. Smith once said he was insulted to be compared to an Old Testament prophet, “because I’m used to being placed much higher in the hierarchy than that.” But he earned the respect of the Māori community through his concern for their welfare. The very archetype of a backblocks doctor, he was also a visionary, an iconoclastic pioneer, a “courageous, tempestuous, extraordinary man.”

To view a 1948 short film documentary on the Hokianga health service, click here.