2019 TAKAHE MONICA TAYLOR POETRY PRIZE – RESULTS AND JUDGE’S REPORT

By Cilla McQueen - takahe magazine | Posted:

The ‘how’ of the 250 entries is as varied as the poets’ age, experience, linguistic ability and knowledge of prosody permit. I looked just as carefully at the ‘why’: what is going on here, what is the poet actually saying?

As finalists I chose four poems, all of which left me something to think about further. They all give a sense of something waiting to be resolved, something not quite sayable, at the limits of language.

HIGHLY COMMENDED:

Two poems dealing with less-acknowledged phases of grief.

Awe by Wes Lee

A poem barely under control after the shock and disorientation of ‘a grave event’; the poet casting around feeling inadequate, trying to come to terms – but far too early – with something disproportionate to previous experience.

Now it is winter by Melissa Browne

One telling visual image, bracketed by stanzas considering the cycle of seasons, time, and memory. The sadness and patience of acceptance and waiting as time passes.

PRIZE WINNERS:

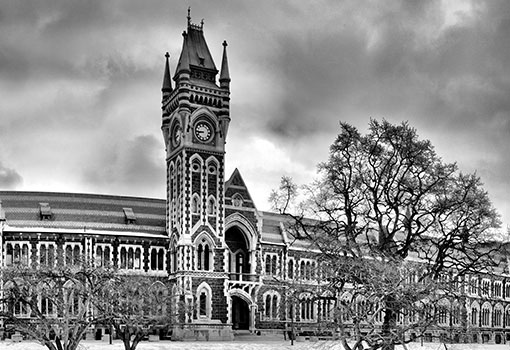

Laying drainage ditches for the new football pitches at Logan Park by Jilly O’Brien

The depth of this poem’s layers presents thought-provoking material. Logan Park is reclaimed land – early Dunedin’s rubble and detritus placed into what was once a bay, part of the inner bowl of Otago Harbour. The (colonial) idea here is that it has been ‘claimed back’ from the sea. This new land was claimed again by the city through naming: at first Pelichet Bay, then Logan Bay, then Logan Park. The poem pivots about two possible meanings of reclamation. It depends on your viewpoint.

The wheke provides a fresh perspective. Chinking handles of broken crockery among the rubbish being cast up by the earthmoving machines might call to mind small tentacles. These ‘wheke’ seem to be calling to the poet, who sees them as old bones coming to light. ‘Ngā wheke cried for their bones back/ for they wanted them to make a cloak/ to wear on the road gangs’. If wheke have no bones, then beyond the paradox, these little visual and sonic tohu could represent ancestral bones calling for recognition. The poem undoes the literal cover-up of the reclaimed land. Old bones of pre-colonial time, wanting to be heard, ask for a different re-claiming, a necessary protection for their descendants in a cloak of mana and safety.

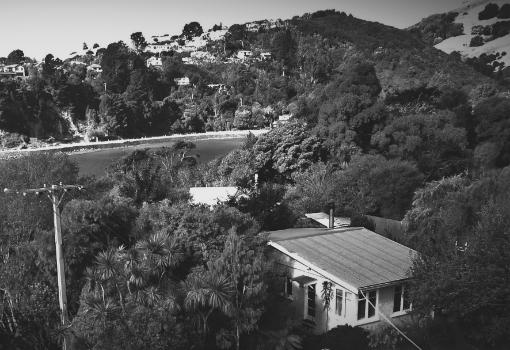

Ninox by Jasmine O M Taylor

In this poem of call and response, ‘we sit alert’ as the soft voice of the hunter/poet reaches gently into the forest and the mind. The pure vowel sounds of the ruru’s call draw the reader into the aural field of the poem, where an alert consciousness which ‘summons perception’ in a willed intensity of listening initiates a thought-journey, inviting us to experience communication with the natural world. I can see and sound those vowels on the page: the poem works with eye and ear, connecting poet, bird and reader. It ends with a feeling of friendship, connection, kin: ‘E hoa, ruru’. The language is simple and direct; not a word is wasted.

Which is the better poem?

Each carries such powerful resonance – aural and historical – that I find it very difficult to separate the two.

IN THE END, THE MUSICAL QUALITY AND QUIET INTENSITY OF ‘NINOX’ WINS

Cilla McQueen

Bluff, 2019

Founded in 1989, takahē magazine publishes short stories, poetry and art, as well as essays, interviews, and book reviews in related areas. Many of Aotearoa New Zealand’s brightest literary talents made their first public appearance within our pages, and we remain committed to publishing the best work from emerging talents alongside that of established writers and artists.

takahē is published three times per year, in print in April and December, and online on this website in August. The first online issue was published on 10 August 2016.

The Takahē Collective Trust is the non-profit organisation behind the magazine, that acts to support and promote writers, poets, artists and cultural commentators. The takahē logo is based on a Māori cave painting, and was gifted to the Takahē Collective by artist John Bevan Ford (1930–2005).